When Code Takes the Stand: The Controversy Surrounding an AI Avatar Arguing in a New York Courtroom

On a brisk morning in Manhattan, a scene unfolded inside a New York courtroom that has since sparked widespread debate across legal, technological, and ethical spheres. An AI-generated avatar—visibly humanoid on a courtroom screen—attempted to argue a case on behalf of a litigant. The avatar, powered by generative AI, was programmed to deliver oral arguments, respond to judicial queries, and reference case law in real time. What began as a bold experiment quickly escalated into a courtroom standoff, raising critical questions about the role of artificial intelligence in the legal system and challenging centuries-old assumptions about legal representation, personhood, and the definition of counsel.

The emergence of AI-driven tools in legal practice is not novel. Over the past decade, artificial intelligence has steadily infiltrated back-office operations in law firms and corporate legal departments. From contract analysis and e-discovery to predictive litigation analytics and automated document drafting, AI’s footprint in the legal domain has grown significantly. Tools like ROSS Intelligence (prior to its legal shutdown), Casetext, and DoNotPay have each, in different capacities, offered AI-powered assistance to lawyers and individuals navigating the legal landscape. Yet, these tools operated within boundaries that respected the human-centered nature of courtrooms. The New York incident shattered that precedent, marking the first time an AI avatar attempted to physically represent a human in a court of law.

At the heart of the incident is a deeply provocative question: Can a machine stand in place of a licensed attorney—or even a self-represented litigant—in a court of law? The implications are both legally complex and socially consequential. Critics argue that allowing AI to act as counsel undermines the legal profession and diminishes the solemnity of judicial proceedings. Proponents counter that AI could dramatically enhance access to justice for underserved populations, especially in civil cases where legal representation is often lacking.

The court’s immediate response to the AI avatar was one of disruption and discomfort. The judge presiding over the case reportedly ordered the AI avatar to be shut off, citing unauthorized practice of law and lack of formal recognition. The incident triggered an emergency review by the New York State Bar Association and reignited national debates over the use of technology in the justice system. Meanwhile, legal ethicists, technologists, and civil rights advocates are voicing sharply divided opinions, with some calling for stricter guardrails and others urging regulatory innovation.

This blog post delves deeply into this unprecedented event, examining its origin, legal context, technical underpinnings, and broader ramifications. It offers a comprehensive overview of the challenges posed by AI’s integration into the legal system and seeks to answer key questions: What legal frameworks exist—or fail to exist—for AI representation? What technologies powered the AI avatar’s courtroom presence? How do ethics intersect with emerging capabilities? And what does this mean for the future of legal practice and access to justice?

As we navigate these questions, it becomes clear that this incident is not just about a single AI avatar or a singular courtroom controversy. Rather, it is a harbinger of transformations to come—transformations that could redefine the nature of legal representation, the boundaries of machine agency, and the contours of judicial procedure in the digital age. In this analysis, we aim to explore not only what happened, but why it matters, and what lies ahead.

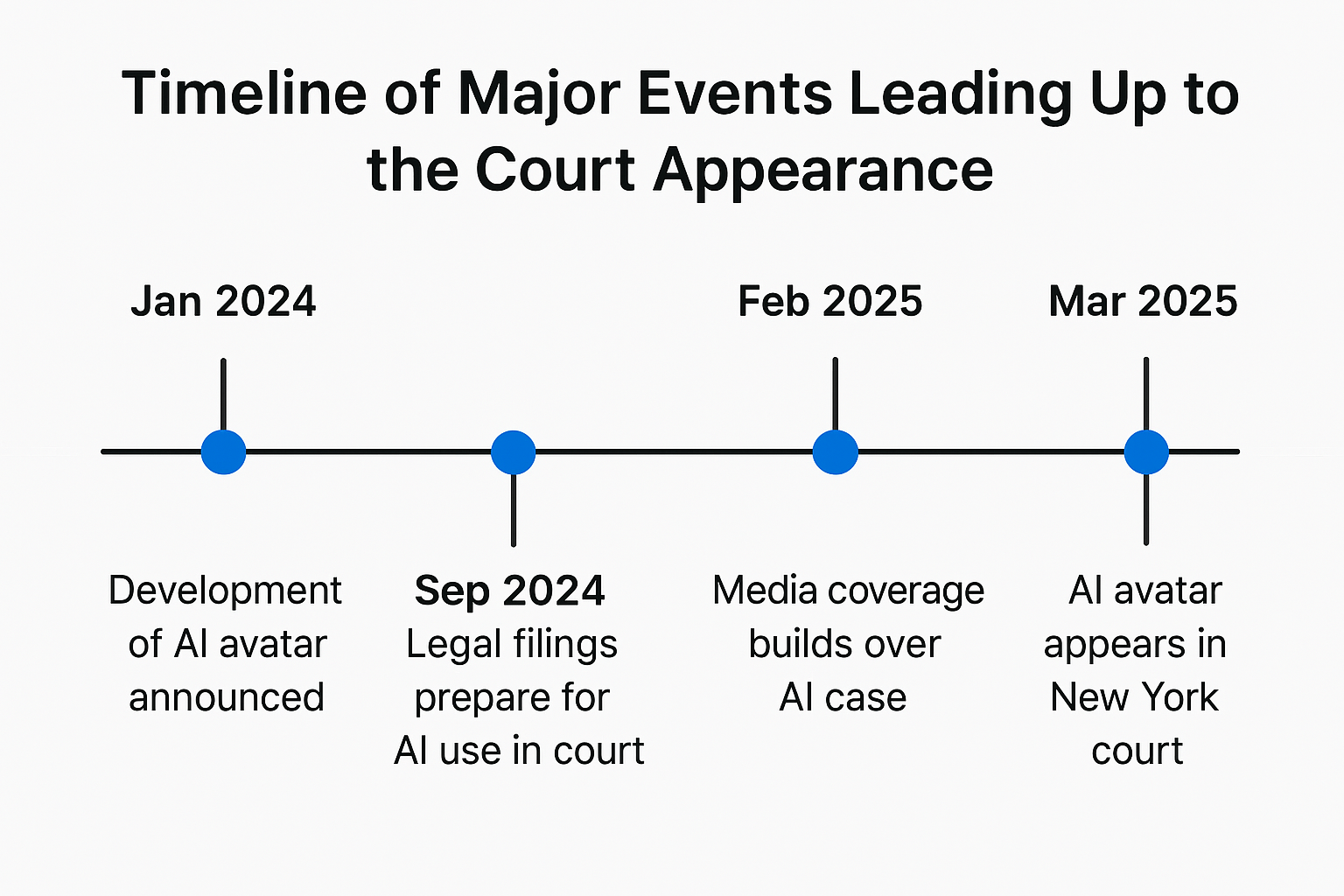

The Event: AI in the Courtroom

On March 11, 2025, a courtroom in Manhattan’s Civil Court became the unexpected setting for a groundbreaking, and ultimately controversial, legal experiment. An AI avatar—resembling a middle-aged professional in attire and demeanor—was projected onto a courtroom screen via videoconferencing technology. This AI-driven entity, created by a private legal-tech startup named LexOmega, was programmed to argue a case on behalf of a small claims litigant in a civil dispute involving tenant–landlord issues. Designed to respond in real time using natural language processing and legal reasoning algorithms, the avatar introduced itself, cited relevant precedents, and attempted to begin opening arguments before the presiding judge intervened.

The case, at its core, was mundane: a dispute over alleged nonpayment of rent and lack of habitable conditions in a rental property. What transformed it into a national talking point was not the content of the case but the identity of the “speaker.” The litigant, a 38-year-old Brooklyn resident named Aaron Mitchell, had partnered with LexOmega to use the AI avatar as a substitute for in-person representation. Mitchell had waived his right to self-representation in a conventional sense and sought to have the AI speak entirely on his behalf. According to Mitchell, the arrangement was born out of necessity: unable to afford legal representation and unfamiliar with legal procedure, he believed the AI could give him a fighting chance in court.

The developers behind LexOmega had trained the AI on thousands of small claims cases from New York’s public legal archives. According to their press briefing after the incident, the system was designed not to practice law per se, but to “assist in procedural navigation and argument formulation for litigants exercising self-representation rights.” The AI avatar itself was equipped with a legal reasoning engine, access to a curated subset of case law, and a user interface that allowed the litigant to monitor its responses in real time. However, the software was not explicitly authorized by any court or judicial body to speak or act as counsel.

From the moment the AI avatar began to speak, the courtroom atmosphere shifted dramatically. The judge, Hon. Elena Navarro, paused the proceedings, questioned the legitimacy of the representation, and requested clarification from Mitchell. Upon learning that the speaking entity was not a licensed attorney nor a human self-representative, Judge Navarro halted the trial and issued a recess. Within hours, media outlets had picked up the story. The news spread quickly: a machine had attempted to argue a legal case in open court.

The legal system’s reaction was swift and unequivocal. The New York State Unified Court System issued a statement later that day clarifying that “only licensed attorneys or self-represented parties may present arguments in court.” It emphasized that “no artificial agent may substitute for human presence in a courtroom under current law.” The court further warned that the incident would be reviewed for potential violations of the rules of professional conduct and court procedure.

The legal community was, unsurprisingly, polarized. Some members of the New York Bar called for immediate disciplinary action against those responsible for facilitating the avatar’s appearance. Others—particularly from the legal tech sector—urged caution, framing the event as an inevitable collision between outdated legal frameworks and emerging technologies. Several tech advocates argued that no law had been explicitly broken, as Mitchell remained the formal party in the case and had effectively used the AI as an interface or prosthetic for self-representation.

Adding fuel to the fire, civil liberties organizations entered the discourse. The New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) released a measured statement urging regulators not to stifle technological experimentation that could advance access to justice. They pointed to studies indicating that over 70% of civil litigants in small claims courts across the U.S. appear without counsel, often resulting in unfavorable outcomes. The NYCLU contended that innovative tools like AI avatars might offer a critical solution to the justice gap—if developed and regulated responsibly.

In contrast, bar associations and judicial oversight bodies emphasized the potential risks of such tools. They pointed to the unauthorized practice of law, the risk of erroneous legal advice, and the inability of AI to grasp nuance, emotion, and ethics. They also raised concerns about accountability: if an AI system provides faulty legal arguments or misrepresents facts, who is liable—the developer, the user, or the machine?

A parallel debate unfolded in the academic sphere. Professors of law and computer science weighed in through op-eds and public lectures. Some characterized the event as premature and ill-advised. Others described it as a necessary disruption that forces legal institutions to reckon with the changing nature of intelligence and advocacy. Professor Amelia Yoon of Columbia Law School remarked, “This is a Rubicon moment. Either we recalibrate the legal system to accommodate technological agents, or we risk alienating a generation for whom AI is an extension of daily life.”

Meanwhile, LexOmega found itself under both public scrutiny and regulatory investigation. Its CEO, Dr. Jordan Lin, defended the deployment by arguing that the company had not misrepresented its tool as a substitute for licensed counsel. In an official statement, Lin said, “Our AI avatar was designed to empower litigants who would otherwise face systemic disadvantage. We respect the court’s position, but we believe the law must evolve to meet the reality of 21st-century challenges.”

The aftermath of the incident has already begun to influence legal policymaking. The New York State Bar Association has scheduled an emergency task force meeting to evaluate the implications of AI tools in court settings. Lawmakers in Albany have proposed new language for the Judiciary Law that would explicitly prohibit or permit AI representation under specific conditions. The U.S. Department of Justice has reportedly begun informal inquiries into the broader implications of automated legal assistance systems.

This single event—a digital avatar uttering opening remarks in a Manhattan courtroom—has illuminated a deep tension between legal tradition and technological evolution. It exposed ambiguities in procedural law, raised urgent questions about equity and access, and thrust the judiciary into a debate for which it was arguably unprepared. As the legal system begins to digest what transpired, the incident will likely become a landmark moment—either a cautionary tale or a harbinger of systemic reform.

Legal Framework: Is AI Allowed to Represent in Court?

The controversy surrounding the AI avatar’s appearance in a New York courtroom is fundamentally rooted in a legal system that, by design, predicates courtroom advocacy on human agency, legal training, and licensure. The event exposed significant gaps and ambiguities in current legal frameworks, especially regarding whether non-human entities—particularly artificial intelligence systems—may participate in, or conduct, courtroom advocacy. To address these questions, it is necessary to examine both the existing legal statutes and the broader jurisprudential principles that govern representation, legal personhood, and the unauthorized practice of law.

Legal Representation in New York: A Human-Centric Framework

Under the current legal regime in the State of New York, representation in court proceedings is strictly reserved for either licensed attorneys admitted to the bar or litigants who choose to represent themselves—commonly referred to as pro se litigants. This is enshrined in several governing authorities, including the New York Judiciary Law, Civil Practice Law and Rules (CPLR), and regulations promulgated by the New York State Unified Court System.

Article 15 of the Judiciary Law, specifically §478 and §484, defines the unauthorized practice of law and prohibits any non-admitted individual or entity from giving legal advice or acting as counsel in legal proceedings. The law is written with human actors in mind, but its language is sufficiently broad to encompass artificial agents as well, since they do not possess bar admission, legal accountability, or moral agency.

Self-representation is permitted under constitutional and statutory law, including under Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment (procedural due process), and Rule 12 of the New York Uniform Civil Rules. However, the right to self-representation is personal and non-delegable. Courts have consistently ruled that litigants may not assign or outsource this role to unlicensed third parties. By analogy, using an AI system to “speak” in court arguably constitutes an impermissible delegation.

The moment the AI avatar began to speak in Judge Navarro’s courtroom, it entered a domain protected by these legal and ethical constraints. While Aaron Mitchell remained the named party in the dispute, his attempt to have a machine serve as his functional representative violated both the letter and spirit of New York’s legal framework.

Definitional Barriers: What Is the “Practice of Law”?

A key issue raised by this incident is the definition of “the practice of law.” Courts across the United States have struggled to offer a precise definition. In Matter of Rowe v. FHP, Inc. (1995), the New York Court of Appeals held that the practice of law includes “the rendering of services for others that call for the professional judgment of a lawyer.” This definition is both functional and elastic, and it allows courts to adapt to new forms of legal service delivery.

The use of an AI avatar—especially one that cites legal precedent, formulates arguments, and responds in real time to questions—clearly falls within this broad scope. Although it is not a human and does not hold a J.D., the avatar’s functionality mimics that of a practicing lawyer, thereby triggering concerns about the unauthorized practice of law.

This concern is not purely academic. In Lola v. Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP (2015), the Second Circuit Court of Appeals emphasized that tasks requiring "a modicum of legal judgment" are reserved for licensed practitioners. Applying this precedent to artificial intelligence suggests that systems exercising even minimal legal reasoning fall within restricted territory.

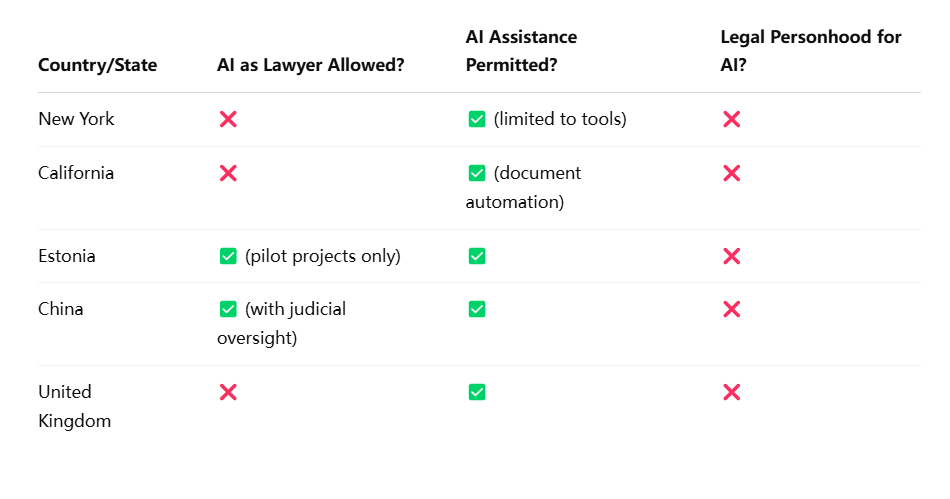

International Comparisons and Emerging Jurisdictions

To assess whether the United States is an outlier in its position, it is instructive to consider developments in other jurisdictions. Although no major legal system currently permits AI to formally argue in court, several have made tentative steps toward integrating AI into legal processes.

For instance, Estonia, often lauded for its digital governance, has piloted a “robot judge” system for adjudicating small claims under €7,000. This system issues rulings algorithmically, although it does not advocate for either party. In China, AI systems such as the "Smart Court" in Hangzhou assist judges in decision-making and allow AI-generated recommendations, but they do not independently represent litigants. The United Kingdom, while technologically progressive in judicial digitization, maintains strict limits on courtroom representation and does not permit AI avatars to argue on behalf of litigants.

These international experiments show growing openness to AI’s procedural assistance—but always under the umbrella of human supervision and responsibility.

The Absence of Legal Personhood

Another reason AI avatars cannot participate in court proceedings is the legal doctrine of personhood. In common law systems, only natural persons and recognized legal entities (e.g., corporations) may possess rights and duties under the law. Artificial intelligence systems, regardless of their sophistication, lack legal personality and are therefore ineligible to act as litigants or representatives.

Attempts to redefine this boundary have thus far been unsuccessful. In 2017, the European Parliament considered proposals to assign “electronic personhood” to highly autonomous AI systems but later shelved the initiative amid widespread legal and ethical pushback. Courts have consistently resisted granting machines any kind of legal standing or capacity to engage in litigation autonomously.

In this sense, even if an AI system were to surpass human capabilities in legal reasoning, it would still lack the necessary juridical status to participate in courtroom procedures unless laws are formally amended to accommodate such a paradigm shift.

Emerging Regulatory Discussions

In the aftermath of the New York incident, regulators and lawmakers are now actively debating whether a new class of legal tools—such as AI avatars—should be carved out under a regulated “legal aid assistant” framework. Some have proposed certification regimes where AI systems could be authorized for specific low-stakes matters, such as landlord–tenant disputes or traffic court, provided they meet rigorous transparency, accountability, and oversight standards.

Critics of such proposals warn that regulatory legitimization may pave the way for corporate overreach, the erosion of the legal profession, and the risk of displacing human judgment. Others see it as a necessary response to a system already strained by chronic underrepresentation, especially among economically vulnerable populations.

Bar associations in California and Illinois have recently formed working groups to study these questions, and several academic institutions are conducting empirical research on how AI-driven legal interfaces impact court outcomes. As of April 2025, however, no U.S. jurisdiction formally authorizes AI systems to act as representatives in legal proceedings.

The legal framework surrounding courtroom representation in New York—and the United States more broadly—remains firmly rooted in human advocacy. Whether through licensed attorneys or self-represented litigants, the act of legal representation is governed by doctrines of personhood, licensure, and ethical accountability. The attempt by an AI avatar to act in this capacity violated several foundational principles and triggered a system-wide reckoning.

Yet the law is not static. As artificial intelligence continues to evolve and its application in legal services becomes more pervasive, courts and lawmakers will face mounting pressure to revisit these doctrines. The question is not merely whether AI can practice law, but whether the law can adapt fast enough to ensure that innovation does not come at the cost of justice, integrity, and due process.

Technical Anatomy: How the AI Avatar Was Built

Understanding the architecture and design of the AI avatar that attempted to represent a litigant in a New York courtroom is essential to evaluating the legitimacy, capabilities, and limitations of such a system. The avatar, developed by the legal technology firm LexOmega, represented a confluence of multiple advanced technologies, ranging from natural language processing (NLP) and speech synthesis to legal data curation and real-time conversational AI. Though it never received formal approval to operate in court, its technical sophistication signifies a major leap forward in the deployment of AI within high-stakes procedural contexts.

Foundational Technology Stack

At its core, the AI avatar relied on a multi-layered architecture consisting of four primary components:

- Natural Language Processing Engine

The system was powered by a customized NLP model based on an open-source large language model (LLM) framework, fine-tuned on a curated dataset of U.S. legal texts. This dataset included civil procedure manuals, small claims court rulings, housing dispute case law, and landlord–tenant regulations specific to New York. By integrating legal lexicons and procedural templates, the model was able to simulate legal argumentation with a degree of fluency approximating junior associates. - Real-Time Speech Generation and Recognition

The avatar featured a speech synthesis module with human-like cadence, designed using a neural text-to-speech (TTS) model. This module allowed the avatar to audibly present arguments and respond to verbal prompts from the judge in real time. A parallel automatic speech recognition (ASR) layer enabled the system to convert spoken questions or interruptions from the bench into textual inputs, which were processed by the NLP engine. - Avatar Visual Interface

The visual component of the AI system was an animated humanoid figure generated using real-time 3D rendering. Designed for neutrality and professionalism, the avatar’s appearance was modeled to reflect conventional courtroom attire and demeanor. Facial animations were synchronized with speech output using facial motion capture software, lending a degree of realism to the experience. While the avatar was not physically present, it appeared live on a courtroom monitor via videoconferencing, behaving as if it were a remote participant. - Legal Decision Support Layer

Perhaps the most novel feature of the system was its integration with a legal decision support engine. This layer contained embedded logic for citing statutes, summarizing relevant precedents, and drawing analogies to historical cases. It operated as a dynamic retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) system, blending pre-trained knowledge with live access to a proprietary legal database. In essence, the AI could not only formulate arguments but justify them with contextually relevant legal sources.

Operational Capabilities and User Interface

From a usability perspective, the AI avatar was designed to be initiated by the litigant via a secure web interface. Once activated, the system prompted the user to input basic case details—such as jurisdiction, case type, and key grievances—using either text or voice. The AI then structured a legal position, drawing from predefined templates and adaptive language models.

During court proceedings, the avatar maintained an active connection to the backend servers via encrypted channels, enabling real-time analysis and response generation. While a supervising interface was provided to the user, including a pause/override button and a live transcript feed, no real-time human oversight was exercised during the courtroom interaction itself. This design decision, as critics later emphasized, contributed significantly to the controversy, as it bypassed established norms requiring human control over legal submissions.

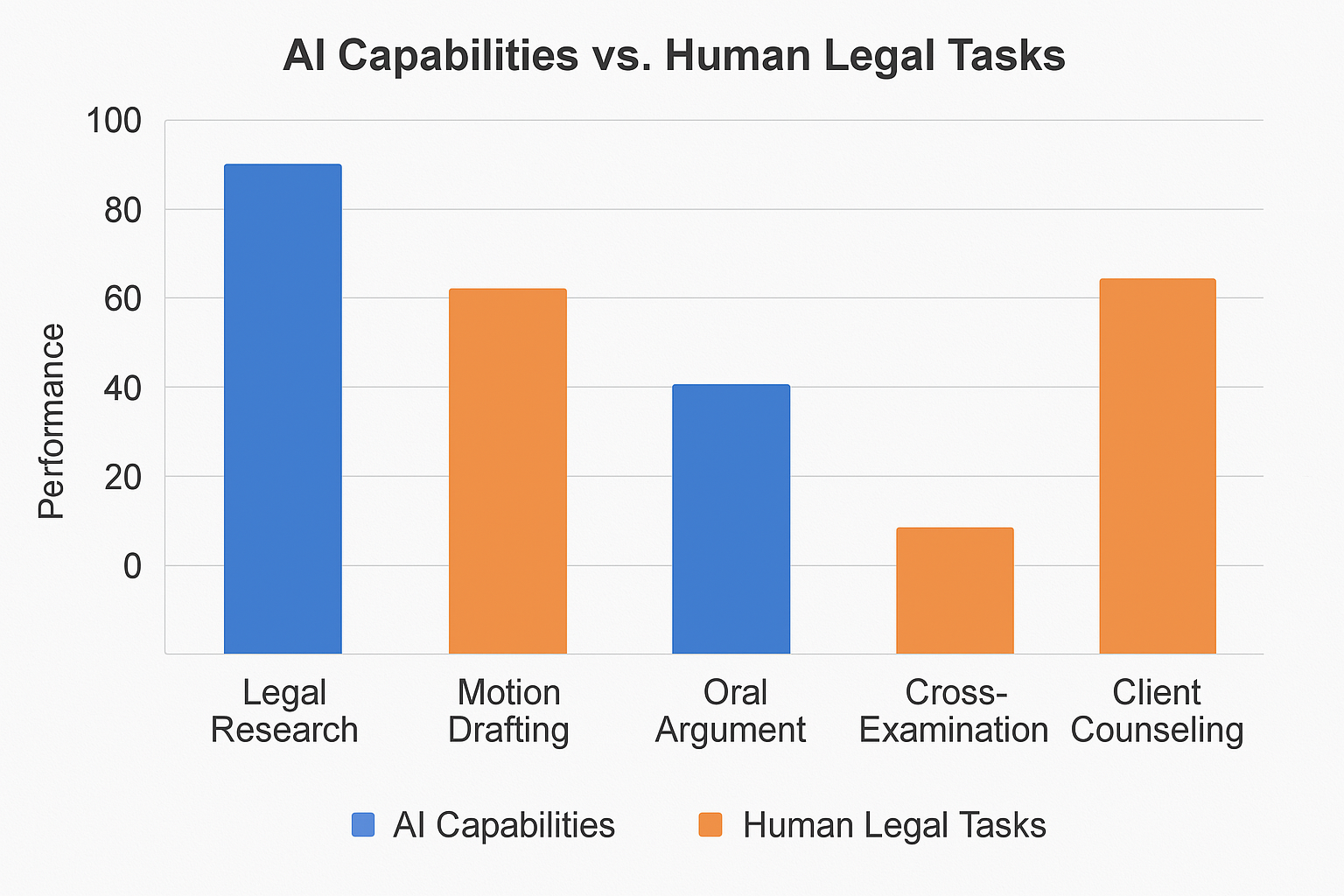

AI Capabilities in Legal Tasks

The AI system’s functionality spanned a wide array of legal tasks. A performance evaluation conducted by LexOmega, and later released to the press, indicated that the system excelled in research-based and procedural operations but fell short in areas requiring discretion and empathy. This breakdown is illustrated in the chart below:

These results underscore the dichotomy between the efficiency of AI in technical tasks and its inadequacy in interpretive or interpersonal domains. While the avatar could retrieve precedents within seconds and quote statute language precisely, it struggled to address off-script judicial interventions and exhibited a lack of adaptability when presented with ambiguity.

Limitations and Known Vulnerabilities

Despite its innovations, the AI avatar possessed several critical limitations:

- Lack of Contextual Judgment: The system’s responses were contingent upon programmed heuristics and lacked situational awareness. If a judge deviated from standard procedure or used figurative language, the AI often misinterpreted the prompt.

- Inability to Understand Emotion: Although it could mimic speech and facial expressions, the AI lacked the capacity to discern emotional cues, thereby failing to adjust tone or strategy based on courtroom dynamics.

- No Legal Accountability: As a non-legal entity, the avatar could not be held liable for inaccuracies or misconduct. This posed ethical concerns, especially in adversarial environments where accountability is foundational.

- Security Risks: Given its reliance on cloud-based systems, the platform was susceptible to latency issues and potential cyber vulnerabilities, particularly during live court proceedings.

Developer Position and Legal Preparedness

LexOmega maintained that the avatar was never intended to serve as licensed counsel but rather as a procedural assistant for self-represented litigants. In their view, the AI functioned more as an augmented reality interface than a legal actor. The company had reportedly sought pre-approval from lower-level administrative staff within the court system but had not received formal clearance from judges or judicial ethics panels. This procedural misstep, combined with the high-profile nature of the courtroom deployment, amplified public and institutional scrutiny.

In response to the backlash, LexOmega announced a temporary moratorium on further court appearances and committed to forming an advisory board comprising legal scholars, ethicists, and technologists to evaluate future deployments. They also opened their codebase to third-party review to enhance transparency.

The AI avatar deployed by LexOmega was an ambitious technological construct that embodied the promise and peril of artificial intelligence in legal practice. With capabilities rooted in advanced language modeling, speech synthesis, and legal data retrieval, it demonstrated that machines could approach certain legal tasks with a degree of competence. Yet, its limitations—chief among them the lack of interpretive judgment, emotional intelligence, and legal standing—reveal the current chasm between technological ability and institutional readiness.

While the avatar’s appearance in a courtroom may have been premature, it offers a critical glimpse into the potential future of augmented legal services. The question now is whether legal frameworks can evolve to responsibly accommodate such tools—or whether they will remain at odds with machines that speak in the language of the law but operate outside its bounds.

Ethical and Philosophical Debates

The attempt by an AI avatar to represent a litigant in a New York courtroom has reignited longstanding debates at the intersection of ethics, philosophy, and technology. While technical and legal discussions tend to dominate initial analyses of such incidents, the deeper implications reside within normative frameworks: What should be the role of artificial intelligence in inherently human institutions like the justice system? Should machines be allowed to speak on behalf of individuals in legal proceedings? Does the involvement of AI in such contexts undermine or enhance human dignity, agency, and fairness?

The incident has not only challenged procedural orthodoxy but has also prompted scholars, ethicists, legal theorists, and technologists to reassess fundamental assumptions about intelligence, agency, and justice. These debates are not only academic in nature; they have direct implications for the design of future AI systems and the governance structures that regulate them.

Arguments in Favor of AI Participation in Legal Processes

Supporters of AI integration in the courtroom make several compelling arguments rooted in accessibility, efficiency, and objectivity.

1. Enhancing Access to Justice

One of the most frequently cited benefits of AI involvement in legal proceedings is its potential to address the persistent and widespread problem of access to justice. In the United States alone, studies have shown that over 75% of civil litigants appear in court without legal representation, often because they cannot afford an attorney. This "justice gap" disproportionately affects low-income communities, immigrants, and marginalized groups.

Proponents argue that AI avatars, if responsibly designed and regulated, could serve as low-cost or even free alternatives to human representation, thereby democratizing access to legal remedies. Unlike traditional legal aid systems—often underfunded and overburdened—AI can operate at scale and offer assistance to large volumes of individuals with minimal incremental cost.

2. Improved Efficiency and Consistency

AI systems, by design, do not fatigue, lose focus, or suffer from scheduling constraints. They can deliver standardized arguments, reference statutes with speed and precision, and operate within defined procedural limits. This operational consistency is seen by many as a way to reduce courtroom delays, eliminate clerical errors, and streamline case management, particularly in high-volume environments such as small claims or traffic courts.

3. Reduced Human Bias

Another argument advanced by AI proponents is that machines—unlike humans—do not carry conscious or unconscious biases. While AI is certainly not free of systemic bias (as it often inherits bias from training data), the hope is that with proper curation and auditing, AI tools could mitigate forms of discrimination that are difficult to eliminate in human judges and attorneys. For example, AI avatars can be programmed to avoid racial, gender, and socioeconomic bias in decision-making logic, thereby contributing to more equitable outcomes.

Arguments Against AI Legal Representation

Despite these potential advantages, critics emphasize that the introduction of AI into legal advocacy raises profound ethical concerns that cannot be overlooked.

1. Erosion of Human Accountability

Legal systems are fundamentally premised on human responsibility. When a lawyer makes an error or engages in misconduct, there are clear lines of accountability—bar associations, licensing boards, and judicial sanctions exist to enforce professional standards. AI systems, however, complicate this framework. Who is liable if an AI avatar misrepresents facts, makes a strategic error, or fails to respond appropriately to a judge's question? Is it the developer, the user, the platform provider, or the system itself?

Without clear mechanisms for accountability, critics argue that AI presence in court undermines the trustworthiness and integrity of judicial proceedings. The absence of a morally and legally accountable agent renders the courtroom interaction ethically hollow.

2. Loss of Human Judgment and Nuance

Legal reasoning is not purely logical or procedural—it also involves judgment, empathy, and the ability to navigate ambiguity. Judges often read body language, evaluate sincerity, and consider the emotional resonance of arguments. These nuances are beyond the reach of current AI systems.

AI avatars, regardless of their technical fluency, cannot fully grasp the socio-emotional context of human litigation. They cannot discern when silence is more effective than speech, when an apology may sway a decision, or when a subtle change in tone signals judicial disapproval. Critics warn that replacing or supplementing human legal actors with AI could strip legal processes of their interpretive depth and moral complexity.

3. Commodification of Legal Advocacy

The deployment of AI avatars by private tech companies introduces another layer of ethical concern—namely, the commodification of legal representation. Critics worry that legal-tech firms, motivated by profit, may prioritize scale and speed over ethical rigor and individualized care. The risk is that vulnerable litigants, drawn by convenience and low cost, may unknowingly place their fate in the hands of systems designed for volume rather than justice.

There is also the danger of AI systems becoming tools for legal exploitation. In theory, automated agents could be used to file frivolous lawsuits at scale, overwhelm opposing counsel with document dumps, or manipulate procedural loopholes—all without ethical restraint.

The Question of Machine Agency

A deeper philosophical question underpins the entire debate: Can a machine be said to possess agency? Agency, in legal and moral philosophy, refers to the capacity of an entity to act with intention and be held responsible for its actions. By most definitions, current AI systems do not meet this standard. They operate based on pre-programmed algorithms, data correlations, and probabilistic modeling. They do not possess self-awareness, intentionality, or moral reasoning.

Some philosophers, such as Luciano Floridi and Thomas Metzinger, argue that extending agency or legal rights to AI systems is both conceptually incoherent and ethically dangerous. Others, such as proponents of “artificial moral agents,” suggest that in limited contexts, AI systems could be treated as quasi-agents—functional substitutes for human actors, though still under human supervision.

The AI avatar in the New York case operated in this ambiguous space. It spoke, argued, and interacted as if it were an agent—but lacked the consciousness or accountability that agency demands. This ontological gray area continues to fuel ethical discomfort and institutional hesitation.

Public Sentiment and Social Trust

Beyond academic discourse, public perception plays a crucial role in shaping ethical norms. Surveys conducted in the wake of the New York courtroom incident reveal a sharply divided public. While some view AI avatars as innovative tools that promote fairness and efficiency, others perceive them as intrusive, inauthentic, or even dystopian.

A majority of judges, according to a preliminary poll conducted by the New York Judicial Council, expressed skepticism toward AI representation in court. Many cited concerns about decorum, professionalism, and the psychological effect on courtroom dynamics. Several noted that they would feel uncomfortable adjudicating cases in which one side was represented by a machine.

This erosion of social trust in judicial processes—if AI is perceived as supplanting human participation—could have long-term consequences. Courts rely not only on legal authority but also on public legitimacy. If that legitimacy is undermined by the introduction of artificial actors, the integrity of the legal system itself may be at risk.

The ethical and philosophical debates surrounding AI participation in the courtroom are as complex as they are consequential. While technological capabilities have advanced rapidly, the normative frameworks governing their deployment remain underdeveloped. Supporters envision a future where AI avatars enhance access to justice, improve efficiency, and promote impartiality. Opponents caution that such visions risk bypassing the foundational principles of accountability, empathy, and human agency upon which the legal system is built.

As the legal community grapples with these questions, one thing remains clear: the integration of AI into the courtroom is not merely a technical issue—it is a moral and societal challenge that demands rigorous, interdisciplinary reflection. The future of justice will depend not just on what AI can do, but on what society should permit it to do.

Broader Implications and Future Outlook

The unexpected appearance of an AI avatar in a New York courtroom is more than an isolated anomaly; it is a signal of systemic transformations on the horizon. As artificial intelligence continues to permeate diverse sectors—from healthcare and finance to education and logistics—its encroachment into the legal domain is both inevitable and deeply consequential. This section explores the broader implications of the courtroom incident, the potential trajectory of AI integration into judicial systems, and the critical institutional, regulatory, and societal responses required to navigate the transition responsibly.

AI as Legal Support Versus Legal Representative

A fundamental distinction in discussions about AI in the legal profession is the difference between legal support tools and legal representatives. AI tools such as legal research platforms, document summarization engines, and contract analyzers have been widely adopted with little controversy. These systems augment human capabilities and remain firmly under human control.

The case of the AI avatar, however, represents a paradigm shift. Here, AI was not a background assistant but a foreground participant—a visible and vocal actor in judicial proceedings. This transition from support to representation marks a pivotal inflection point, prompting institutions to reconsider the roles machines may play in highly formal, adversarial, and morally weighted environments.

While some experts advocate for expanding AI’s role in low-stakes matters, others argue for the establishment of bright-line rules that maintain human exclusivity in courtroom advocacy. As jurisdictions contemplate these questions, the creation of a legal category akin to “AI-assisted representation” may offer a middle path. Such a framework could permit the use of AI tools under strict human supervision, preserving the integrity of legal practice while improving access and efficiency.

Impact on Legal Education and Professional Roles

If AI systems continue to gain traction in legal processes, the implications for legal education and the structure of professional roles will be profound. Traditional legal training emphasizes doctrinal analysis, rhetorical skill, and the capacity to synthesize precedent. While these skills will remain valuable, new competencies in technology management, AI oversight, data ethics, and algorithmic accountability will become equally essential.

Law schools may be compelled to revise curricula to include courses on legal technology, coding literacy, and the philosophy of artificial intelligence. Bar associations could introduce continuing legal education (CLE) requirements that mandate training in AI governance and legal tech tools. Moreover, a new class of professionals—legal technologists, AI compliance officers, and judicial innovation specialists—may emerge to bridge the gap between law and machine intelligence.

Judicial Infrastructure and Institutional Readiness

The incident has also exposed shortcomings in judicial infrastructure and institutional readiness. Courts across the United States—and indeed, across the world—were not designed to accommodate artificial agents as participants in litigation. Existing case management systems, rules of evidence, codes of conduct, and courtroom procedures assume the presence of human actors operating within a shared moral and cognitive framework.

To prepare for future disruptions, court systems must invest in both technical infrastructure and regulatory foresight. This may include:

- Updating courtroom technology to securely integrate digital and AI elements.

- Establishing ethical guidelines and review panels for AI applications in litigation.

- Creating sandbox environments for controlled experimentation with AI in adjudicatory settings.

- Instituting procedural safeguards to ensure due process is not compromised by AI interventions.

Notably, international bodies such as the European Commission and the Hague Conference on Private International Law have begun issuing preliminary frameworks for AI in dispute resolution, signaling an emerging consensus on the need for proactive governance.

Regulatory Innovation and Risk Management

As AI tools become more embedded in legal workflows, governments and regulatory agencies will need to craft nuanced legal frameworks that address emerging risks while enabling innovation. This regulatory architecture must address several core questions:

- Under what conditions, if any, can AI serve as a litigant’s voice in court?

- What standards of transparency and explainability must AI systems meet to be deemed reliable?

- How should liability be allocated in cases where AI systems cause harm or error in judicial proceedings?

One potential solution is the creation of a certification regime for courtroom AI, akin to the FDA’s regulation of medical devices. Under such a model, AI systems would be subject to rigorous testing, continuous monitoring, and clearly defined scopes of permissible use. Unauthorized or uncertified deployment—such as the avatar in the New York case—could then be penalized under revised statutes prohibiting the unauthorized practice of law by nonhuman entities.

International Convergence and Divergence

While legal systems vary significantly across jurisdictions, the global nature of technology development necessitates a degree of international convergence in legal AI governance. Cross-border legal practice, international arbitration, and transnational commerce all raise questions about the interoperability of AI tools and the consistency of legal standards.

Some countries—such as Estonia, Singapore, and China—have already launched pilot programs for AI-integrated courts. These initiatives offer valuable case studies for more conservative jurisdictions. However, divergence in cultural attitudes toward authority, agency, and legal formality may lead to asynchronous adoption, with some legal systems embracing AI at scale and others resisting systemic change.

Coordination among global regulatory bodies, including the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) and the International Bar Association (IBA), will be essential to prevent regulatory arbitrage and ensure that ethical standards are upheld across borders.

Potential for Misuse and Adversarial Exploits

As AI becomes more capable, so too does its potential for misuse. Legal scholars have warned of “adversarial AI” scenarios in which systems are weaponized to game legal processes, file frivolous claims en masse, or manipulate judicial outcomes through data-driven influence operations. The legal system must therefore develop robust cybersecurity protocols, data provenance safeguards, and audit mechanisms to ensure that courtroom AI cannot be exploited for malicious purposes.

Moreover, there is a risk of algorithmic entrenchment, where AI systems trained on historically biased data perpetuate or even exacerbate inequities. Without transparent and accountable design, AI tools could encode systemic discrimination into their operations, undermining the very goal of justice they purport to serve.

Long-Term Societal Implications

The symbolic and psychological ramifications of machine actors in court cannot be overstated. Courts serve not only as instruments of adjudication but also as rituals of civic engagement, public morality, and societal validation. The presence of AI in such spaces raises important questions about the human experience of justice. Will litigants feel genuinely heard if addressed by a machine? Will verdicts carry the same moral weight if influenced or delivered by an algorithm?

There is a risk that over-reliance on AI could erode the interpersonal dimension of law, reducing complex human conflicts to procedural outputs. Conversely, if designed with ethical foresight and careful constraint, AI could also serve to enhance human dignity, by ensuring that no litigant goes unheard, unrepresented, or unprotected.

The courtroom deployment of an AI avatar has unveiled the legal system’s simultaneous vulnerability and adaptability in the face of technological disruption. As the legal community deliberates on next steps, it must balance innovation with prudence, efficiency with equity, and automation with accountability. The broader implications are not confined to any single case, jurisdiction, or profession—they touch upon the very future of justice itself.

Whether AI becomes a co-counsel, a procedural assistant, or a regulated presence in court, its integration must be guided by clear principles, robust institutions, and a collective commitment to upholding the rule of law in an era defined by machine intelligence. The choices made today will determine whether tomorrow’s legal systems are more inclusive and effective—or more fragmented and opaque.

Conclusion

The attempt by an AI avatar to represent a litigant in a New York courtroom is emblematic of a broader confrontation between technological advancement and institutional tradition. While the incident may appear at first glance to be a novelty or a fringe event, its implications are far-reaching. It challenges deeply embedded legal doctrines, exposes vulnerabilities in regulatory preparedness, and prompts a necessary reevaluation of the human-machine relationship within the realm of justice.

This event has illuminated the tension between aspiration and regulation—between the promise of democratized legal access through artificial intelligence and the essential requirements of accountability, personhood, and procedural integrity. As the legal profession stands at a technological crossroads, it must ask whether existing doctrines are adequate to address emerging realities or whether a new jurisprudence must be crafted to govern the era of intelligent systems.

Throughout this blog, we have explored the legal parameters that currently prohibit nonhuman entities from engaging in courtroom advocacy. We have examined the technical anatomy of the AI avatar and assessed its strengths and weaknesses. We have navigated ethical debates around autonomy, responsibility, and fairness, and considered the broader implications for education, regulation, and public trust in the justice system.

What becomes evident is that the issue is not one of mere technological readiness, but of institutional will and societal values. The question is not only what artificial intelligence can do, but what we—collectively, as a legal and civic society—should permit it to do. If the goal of the legal system is to uphold justice, dignity, and truth, then any integration of AI must be subordinate to those ends, not merely efficient in their execution.

As policymakers, educators, technologists, and jurists deliberate the path forward, it is imperative that their approach be grounded in humility, transparency, and inclusiveness. This moment offers an opportunity not only to modernize legal infrastructure but to reaffirm foundational democratic principles in the face of algorithmic change.

In the final analysis, the courtroom appearance of an AI avatar may well be remembered as a catalyst—a moment that forced a centuries-old institution to look in the mirror and reckon with a future it can no longer ignore.

References

- OpenAI – GPT and Legal Applications

https://openai.com/research/gpt-legal-applications - American Bar Association – Ethics of AI in Legal Practice

https://www.americanbar.org/groups/science_technology/publications/ethics-of-ai/ - New York State Unified Court System – Rules and Procedures

https://www.nycourts.gov/rules/ - Stanford HAI – AI and the Future of Legal Services

https://hai.stanford.edu/research/ai-future-legal-services - The Berkman Klein Center at Harvard – Algorithms and Justice

https://cyber.harvard.edu/research/algorithms-and-justice - European Commission – Guidelines on Trustworthy AI

https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai - Legal Services Corporation – The Justice Gap Report

https://www.lsc.gov/initiatives/justice-gap - IEEE – Ethically Aligned Design for Autonomous Systems

https://ethicsinaction.ieee.org/ - MIT Technology Review – AI in the Courtroom

https://www.technologyreview.com/topic/ai-in-the-courtroom/ - World Economic Forum – AI Governance in Legal Systems

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/ai-governance-legal-systems/