Meta's Copyright Win Sparks Legal Uncertainty Over AI Training Data

In a significant development at the intersection of artificial intelligence and copyright law, Meta Platforms Inc., the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, recently secured a major legal victory in the United States. A federal judge dismissed a high-profile copyright lawsuit brought by a group of prominent authors who accused the tech giant of unlawfully using their copyrighted books to train its large language models (LLMs), specifically its LLaMA (Large Language Model Meta AI) family of AI systems. The ruling, handed down by Judge Vince Chhabria of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, marks a pivotal moment in a rapidly evolving area of jurisprudence—where the ambitions of AI developers clash with the rights of human creators.

At the heart of the lawsuit were allegations that Meta, like many AI firms, used publicly available datasets containing copyrighted works without authorization or licensing agreements. Plaintiffs, including authors Sarah Silverman, Richard Kadrey, and Christopher Golden, contended that Meta’s scraping and ingestion of their books into its model architecture constituted direct copyright infringement. However, the court’s ruling did not offer an explicit endorsement of Meta’s practices. Instead, it found the plaintiffs’ case to be legally insufficient, citing a lack of concrete evidence showing how their specific works had been copied, stored, or materially reproduced in Meta’s output.

This decision follows a growing number of copyright-related lawsuits challenging the legal underpinnings of generative AI, which relies on vast corpora of text, image, audio, and video data to create human-like outputs. From ChatGPT to Midjourney, models across the AI landscape have been trained on large volumes of internet data—raising questions about the legality of using copyrighted content without consent. In recent months, courts have grappled with whether such practices fall under the doctrine of fair use, and what thresholds of evidence are necessary to bring a successful copyright claim in the AI age.

In this particular case, Judge Chhabria ruled that the authors’ claims were overly broad and lacked specificity. Notably, the court emphasized that the plaintiffs had failed to demonstrate a direct nexus between their copyrighted books and Meta’s AI outputs. Without such substantiation, the judge determined that the allegations could not survive summary judgment. While the ruling represents a procedural win for Meta, it leaves several substantive questions about copyright, fair use, and AI model training unresolved. Importantly, the court’s decision does not preclude future lawsuits that may be supported by more precise allegations and technical documentation.

The implications of this ruling extend far beyond the courtroom. For AI developers, the decision offers temporary relief and perhaps a clearer path forward in training foundational models. For authors, publishers, and creative professionals, it raises alarms about the fragility of intellectual property protections in an era where synthetic content is increasingly prevalent. The case also reflects a broader societal tension between two competing imperatives: enabling technological innovation through open data access and preserving the economic and moral rights of content creators.

Moreover, this case serves as a critical test of how U.S. courts interpret the bounds of fair use in the context of generative AI. Historically, fair use has protected transformative applications of copyrighted works—such as academic research, parody, or news reporting. Whether training a machine learning model qualifies as “transformative” use remains a central legal ambiguity. Judge Chhabria sidestepped a definitive ruling on this matter, focusing instead on the procedural weaknesses of the plaintiffs’ case. Nevertheless, his commentary acknowledged the seriousness of the unresolved questions, and implicitly invited more rigorous legal challenges in the future.

As the legislative and regulatory environment around AI continues to evolve, cases like this are setting precedents—both legal and cultural—that will shape the development and deployment of generative technologies. Industry stakeholders, legal scholars, and public policymakers are all closely watching these developments to determine how best to balance innovation with rights protection. Meanwhile, creators are organizing, tech companies are adapting their legal strategies, and courts are slowly building a framework to adjudicate these novel disputes.

In this blog post, we will explore the Meta copyright ruling in depth. The analysis will proceed in several stages. First, we will delve into the legal context that frames the dispute, including the role of the fair use doctrine and precedent cases. Second, we will examine the court’s reasoning and compare it with similar rulings in other AI-related copyright cases. Third, we will analyze stakeholder reactions and industry responses to the decision. Fourth, we will explore the broader implications of the ruling for the future of AI model training, creator rights, and intellectual property. Finally, we will conclude with an outlook on what comes next—both in the courts and in the evolving landscape of AI governance.

By the end of this analysis, readers will gain a comprehensive understanding of the legal, technological, and ethical dimensions of Meta’s copyright win, and how this moment reflects the broader struggle to define ownership, originality, and accountability in the age of artificial intelligence.

Legal Context: Fair Use & Market Harm

The legal framework surrounding copyright law in the United States, particularly as it relates to artificial intelligence, is undergoing a period of rapid transformation and scrutiny. At the center of the Meta lawsuit is the contentious issue of whether using copyrighted materials for training AI models constitutes fair use. In adjudicating the claims brought forth by a group of authors, Judge Vince Chhabria emphasized that while the plaintiffs had raised valid theoretical concerns, they failed to support their allegations with sufficient legal and factual specificity. This outcome rests not only on the procedural deficiencies of the plaintiffs’ filings but also on the complex and evolving nature of fair use jurisprudence in the AI era.

Foundations of Fair Use in U.S. Copyright Law

The fair use doctrine, codified under Section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act, provides a critical legal mechanism that allows limited use of copyrighted materials without the rights holder’s permission. It is designed to promote freedom of expression and the dissemination of knowledge, balancing the exclusive rights granted to authors with the public’s interest in accessing and using information. The statute outlines four key factors that courts must consider when evaluating fair use claims:

- The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes, and whether the use is transformative;

- The nature of the copyrighted work, such as its factual versus creative content;

- The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

These factors are not applied mechanically, but rather weighed holistically based on the circumstances of each case.

In the context of generative AI, these considerations take on new dimensions. Developers of AI systems typically ingest massive volumes of data—including books, articles, and websites—to teach their models how to understand and generate human-like language. Critics argue that such practices amount to unlicensed copying, especially when the source material includes entire books or collections. Proponents counter that the use is transformative and necessary for machine learning, and that the outputs do not resemble the inputs in any substantial or infringing way.

Judge Chhabria’s Interpretation: An Issue of Evidence, Not Endorsement

In the Meta case, the court did not directly engage in a full fair use analysis under the four factors. Instead, Judge Chhabria concluded that the plaintiffs’ claims could not move forward due to insufficient evidence. He found that the authors failed to show how their works had been specifically used or copied during the AI training process. Notably, the court did not determine whether Meta’s use was fair or unfair under the law—it merely concluded that the authors had not pleaded their claims with adequate detail.

This distinction is critical. The ruling should not be misconstrued as a blanket validation of using copyrighted content in AI training. Rather, it underscores the procedural bar plaintiffs must meet when asserting infringement. Without proving direct copying, substantial similarity in outputs, or market harm, copyright claims are unlikely to survive judicial scrutiny.

Judge Chhabria explicitly acknowledged the potential merit in the broader arguments against AI training on copyrighted content. He stated that while the plaintiffs “may be right” in principle, they “failed to plausibly allege it.” This leaves open the possibility of future claims advancing, provided they are better substantiated with technical and economic evidence.

Comparative Case Law: Anthropic and Google as Legal Precedents

To contextualize the Meta ruling, it is useful to examine two relevant legal precedents: Authors Guild v. Google, Inc. and Doe v. Anthropic PBC.

In Authors Guild v. Google, the court upheld Google’s scanning of millions of books for its Google Books project as fair use. The court emphasized the transformative nature of the project, which enabled search and indexing functions not available in the original works. Despite the complete reproduction of copyrighted books, the use was deemed fair because it added new utility and did not serve as a substitute for the originals.

Similarly, in the more recent Doe v. Anthropic, another judge—William Alsup—dismissed copyright claims on the grounds that the plaintiffs had not demonstrated output-based infringement. Like in the Meta case, the court found that merely alleging that AI models had access to copyrighted works was insufficient. What mattered was whether the models could regurgitate those works in a way that affected market value or consumer demand.

These rulings collectively suggest that U.S. courts are demanding more than general claims of infringement. They require plaintiffs to establish a tangible causal link between ingestion of copyrighted material and harmful output or market substitution.

The “Transformative Use” Debate in AI Training

One of the most contentious aspects of applying fair use to AI model training is the notion of “transformative use.” In traditional fair use cases, courts look for whether the new use adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, and does not simply supersede the original. Transformative uses are more likely to be considered fair.

AI developers argue that training a language model on a dataset comprising copyrighted works is fundamentally transformative. The models do not store or reproduce the text verbatim (in most cases), but rather use the data to learn linguistic patterns, associations, and statistical correlations. The resulting outputs are novel compositions—albeit probabilistically generated based on prior examples.

Critics dispute this framing. They argue that the scale of ingestion and the commercial objectives behind AI systems, particularly those deployed in products and monetized by tech giants, demand more rigorous scrutiny. Moreover, they contend that without licensing, such uses strip authors of compensation while commodifying their intellectual contributions.

The Market Harm Factor: The Authors’ Missed Opportunity

Perhaps the most damaging shortcoming in the plaintiffs’ case was their inability to demonstrate economic harm. Under the fourth fair use factor, market substitution or dilution is often decisive. If an unauthorized use negatively affects the potential market for a work or its derivatives, courts are less likely to view it as fair.

In this instance, the authors failed to present evidence that Meta’s LLaMA models diminished the commercial value of their books, competed with their distribution channels, or undermined potential licensing opportunities. Without such market impact data, their case lacked a core pillar of modern copyright litigation.

This does not mean that market harm cannot be shown in future cases. For example, if an AI model produces summaries or mimics the writing style of a copyrighted work in a way that replaces the original in academic, entertainment, or educational contexts, courts may be persuaded that a form of substitution has occurred. That scenario, however, would require detailed forensic and economic analysis—far beyond what was offered in the Meta lawsuit.

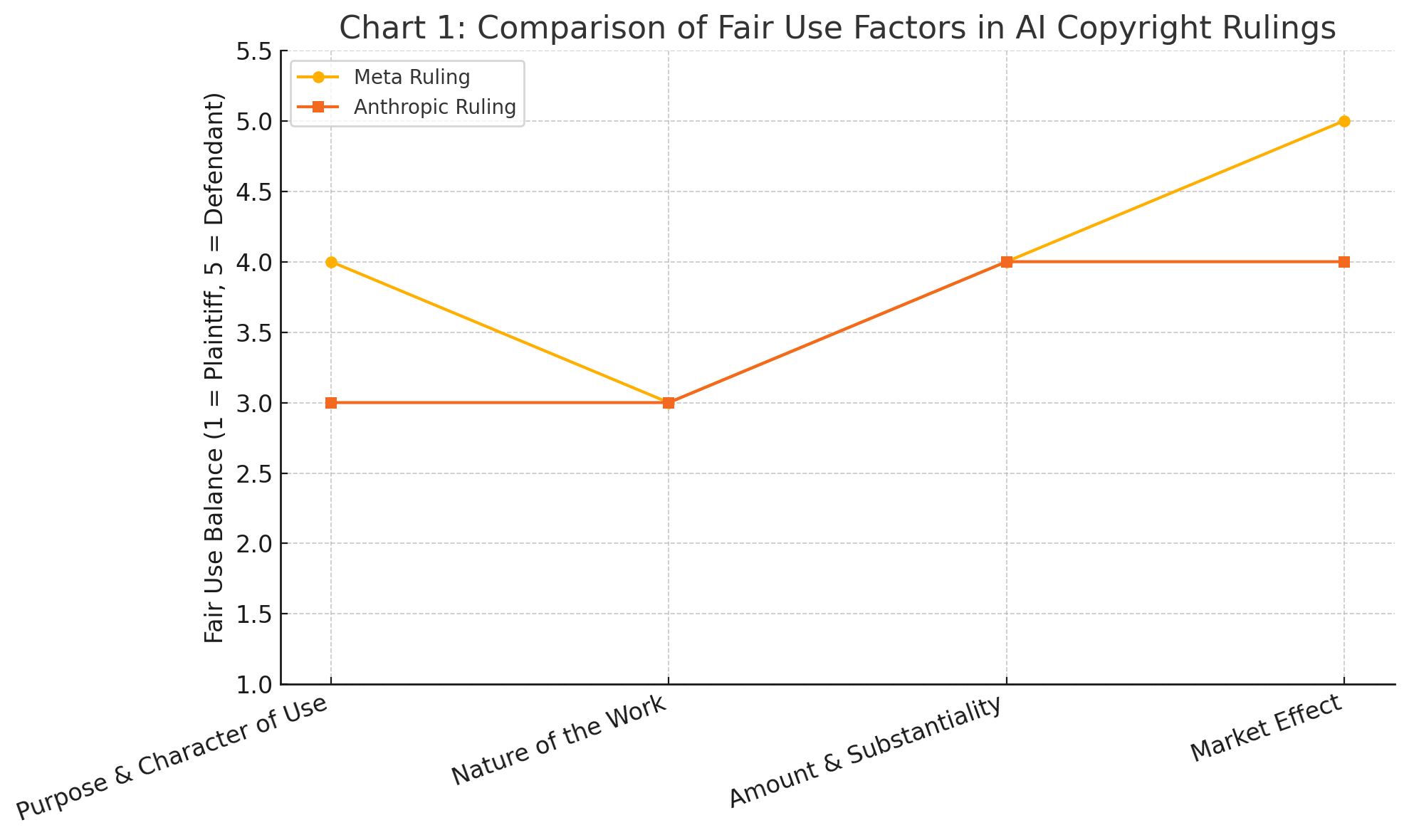

This chart visually contrasts how courts weighed the four fair use factors in the Meta and Anthropic copyright lawsuits. While both rulings favored the defendants, the Meta ruling placed slightly more emphasis on the “market effect” and “purpose” as supporting fair use, reinforcing the procedural—not substantive—nature of the plaintiffs’ shortcomings.

Reactions & Stakeholder Perspectives

The U.S. District Court's dismissal of the copyright lawsuit against Meta ignited a wave of responses from across the technology, legal, publishing, and creative communities. While Meta and others in the AI industry welcomed the decision as a validation of their innovation models, rights holders and legal advocates expressed concern over what they perceive as an erosion of intellectual property protections in the age of generative AI. The divergent perspectives on this ruling not only reflect ideological divides but also illustrate the lack of consensus on how to reconcile the interests of content creators with those of AI developers.

The Plaintiffs’ Response: "A Dangerous Precedent"

The legal team representing the plaintiffs, led by the prominent law firm Boies Schiller Flexner, responded sharply to Judge Chhabria’s ruling. In their public statement, the attorneys emphasized their disagreement with the court’s findings, asserting that the decision set a “dangerous precedent” that undermines the rights of authors. They noted that Meta did not deny using copyrighted works for training its LLaMA models, and argued that the court overlooked clear evidence of unauthorized use.

“We believe the court’s dismissal reflects a failure to grasp the implications of mass scraping and unlicensed data usage in training powerful generative models,” the legal team stated. “The record contains indisputable evidence that our clients’ copyrighted works were used without permission.”

The plaintiffs also signaled their intent to revise and refile their claims, potentially strengthening their arguments with more robust technical data. Their response underscores the broader strategy among authors and creators to continue legal challenges until a court substantively addresses whether AI training constitutes copyright infringement—not just whether it was pled adequately.

Meta’s Stance: Innovation Within Legal Boundaries

From Meta’s perspective, the court’s dismissal of the case reinforced the company’s long-standing position that the training of AI models using publicly available data falls within the scope of fair use. In a brief public statement, Meta reiterated its belief that the development of cutting-edge generative AI requires access to diverse training data, and that such use is protected under existing U.S. copyright doctrine.

“This ruling affirms our commitment to responsible AI innovation,” a Meta spokesperson said. “Fair use is a foundational legal principle that enables transformative technologies while balancing the interests of original creators.”

Internally, the company has emphasized the importance of legal clarity and continues to invest in compliance frameworks to mitigate litigation risk. However, observers note that Meta’s tone remains cautious; the ruling was procedural rather than substantive, and future legal challenges—better formulated—could yield different outcomes.

Industry Reactions: A Divided Landscape

The broader AI industry largely celebrated the decision, viewing it as a moment of judicial restraint that enables continued innovation without immediate disruption. Leading AI developers—including Anthropic, OpenAI, and Google DeepMind—have faced similar lawsuits, and they interpreted the Meta ruling as a possible indication that U.S. courts may require a high threshold of evidence before allowing such cases to proceed.

“We welcome the court’s recognition that vague allegations are insufficient grounds to stall progress in AI,” said a policy advisor at a prominent AI lab. “That said, we acknowledge the need for clear norms and best practices for training data acquisition moving forward.”

In contrast, the publishing and media sectors expressed disappointment and concern. The Association of American Publishers (AAP) issued a formal statement lamenting the court’s decision, warning that it “sends a troubling signal to content creators whose livelihoods depend on enforceable rights over their work.” Similarly, several independent author organizations and creative unions reiterated calls for stronger legal protections, clearer licensing models, and statutory updates that explicitly address the use of copyrighted content in machine learning.

Legal Scholars and Analysts: Nuanced Evaluations

Legal analysts were quick to point out that while the ruling represents a procedural win for Meta, it does not resolve the central legal question of whether AI model training on copyrighted content constitutes fair use. Professor Pamela Samuelson of UC Berkeley noted that “Judge Chhabria carefully avoided reaching a substantive fair use conclusion, focusing instead on the inadequacy of the pleadings.” She added that the ruling should not be viewed as an outright victory for AI developers, since more thoroughly developed cases could still pose a threat.

Other experts emphasized the implications for future litigation strategy. “The takeaway for plaintiffs is that specificity matters,” said Jonathan Band, an intellectual property attorney. “Generic claims will not survive. Future cases must establish not just that copyrighted works were ingested, but also that they caused identifiable market harm or were reproduced in an infringing way.”

The academic community is also increasingly involved in advising policymakers and regulators on how to modernize copyright frameworks to reflect new technological realities. Several law schools, including Stanford and NYU, have launched dedicated research initiatives focused on the intersection of AI, data rights, and copyright law.

Stakeholder Perspectives on the Meta Ruling

Below is a table summarizing the reactions of key stakeholders across different sectors.

| Stakeholder | Position on Ruling | Key Quote / Action |

|---|---|---|

| Plaintiffs (Authors) | Strongly Opposed | “Indisputable evidence of piracy was ignored.” |

| Boies Schiller Flexner (Law Firm) | Disagrees with dismissal | Plans to refile with additional technical documentation. |

| Meta | Supports ruling, emphasizes fair use | “This ruling affirms our commitment to responsible AI innovation.” |

| AI Developers (Anthropic, OpenAI) | Cautiously optimistic | “A welcome reminder that speculative claims aren’t enough.” |

| Association of American Publishers (AAP) | Disappointed, warns of precedent | “Troubling signal to content creators.” |

| Legal Scholars | Mixed, emphasize procedural basis | “Substantive questions remain unanswered.” |

| Independent Creators | Concerned about weakening IP protections | Advocating for statutory reforms and new licensing frameworks. |

Broader Social Perceptions

Outside of legal and industry circles, the ruling also resonated with a broader audience of creators, educators, and journalists. Many social commentators on platforms like X (formerly Twitter) and LinkedIn voiced frustration at what they saw as a judicial failure to protect artists and authors from being “harvested” for corporate machine learning projects. Others, however, applauded the court’s restraint, arguing that obstructing AI research through aggressive litigation would stifle innovation and technological progress.

This divergence of public opinion reflects a deeper societal debate: should training a machine on publicly available content be regulated the same way as direct copying and republication? And if not, what new frameworks are needed to ensure fairness for both innovators and originators?

Implications for AI, Creators & the Intellectual Property Landscape

The dismissal of the copyright lawsuit against Meta has far-reaching consequences, not only for the parties directly involved but also for the broader AI ecosystem, the creative community, and the global legal and policy environment surrounding intellectual property. Although the court’s ruling was based on procedural grounds, it indirectly clarified several legal ambiguities and triggered a wave of reassessment regarding best practices, regulatory gaps, and economic models in the age of generative AI.

For AI Developers: A Green Light—But With Caution

For developers of generative AI systems, the ruling offers what appears to be a temporary reprieve. The legal uncertainty that has loomed over AI model training practices, particularly concerning the use of copyrighted data scraped from the web, has not been eliminated, but it has been pushed back. The court did not declare the training of AI models on copyrighted content to be fair use—nor did it affirm the legality of such practices in general. Instead, it highlighted the need for plaintiffs to bring specific, well-supported claims.

AI companies such as Meta, OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google may interpret this decision as judicial restraint, suggesting that courts are not eager to hinder the momentum of AI innovation unless strong evidence of infringement and harm is presented. However, this does not mean that developers are now shielded from future litigation. In fact, the ruling may encourage plaintiffs to enhance their technical sophistication, strengthen their factual claims, and file narrower, more targeted lawsuits.

As a result, AI developers are increasingly adopting more transparent practices regarding dataset composition, licensing arrangements, and training methodologies. Some firms are already engaging in “data provenance” tracking—using internal documentation to establish where their training data originates, whether it includes copyrighted content, and under what conditions it was acquired. While these practices may not be legally required at this stage, they serve as important risk-mitigation strategies and demonstrate a willingness to engage with the ethical dimensions of AI development.

For Creators: Legal Disappointment, Strategic Recalibration

For authors, artists, and other content creators, the Meta ruling is undoubtedly a setback—but not a final defeat. The court’s refusal to engage with the substantive merits of the case has left the door open for future litigation, provided that plaintiffs can meet the evidentiary burden. That means creators now face a critical juncture: either retreat and accept the growing use of their content in AI training without compensation, or regroup, gather stronger evidence, and return to court with renewed legal vigor.

Key to this strategy will be the ability to demonstrate market harm—a central pillar of copyright law. Creators and their legal teams must work to show that AI models trained on their content either substitute for their works in consumer markets or significantly diminish licensing opportunities. For example, if a generative model can produce summaries, imitations, or excerpts that compete with the original, or if a publisher declines to license a work because a synthetic alternative exists, then the argument for economic damage becomes substantially stronger.

In parallel, advocacy groups are intensifying efforts to introduce voluntary or statutory licensing regimes for training data. Such frameworks would allow AI firms to access copyrighted materials in exchange for reasonable compensation, similar to collective licensing systems used in the music and publishing industries. Organizations like the Author’s Guild, PEN America, and various rights collectives are exploring how to adapt these systems for large-scale, automated data use.

Policy & Regulatory Developments: A Global Patchwork

Beyond the courtroom, the Meta decision has implications for regulatory frameworks and legislative efforts aimed at governing the intersection of AI and copyright. In the United States, the U.S. Copyright Office and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) have initiated public consultations and hearings to understand the needs of stakeholders and explore whether new rules are necessary. However, given the jurisdictional limits of courts and the slow pace of Congress, major reforms remain uncertain in the short term.

Nevertheless, multiple policy trajectories are emerging. Some legislators have proposed bills that would require transparency in training data, mandate opt-outs for rights holders, or establish collective licensing schemes. Others advocate for AI-specific copyright carve-outs, especially when the use is deemed highly transformative and does not result in direct substitution. These debates remain ongoing and are likely to intensify in response to further litigation outcomes and technological advancements.

Internationally, the regulatory picture is even more fragmented. In the United Kingdom, for example, the Intellectual Property Office is developing a voluntary code of practice for the use of copyrighted content in AI training, while in the European Union, the AI Act includes provisions related to training transparency and data usage obligations. China, meanwhile, has implemented stricter content moderation rules for generative AI but has not clarified copyright implications in detail.

This global divergence means that multinational AI firms must navigate a patchwork of legal environments, balancing compliance with innovation and ensuring consistency across product offerings deployed in different jurisdictions.

Emerging Economic Models: Toward Licensing and Value-Sharing

Another significant implication of the Meta ruling is its influence on emerging business and economic models around AI training and creative content. As litigation underscores the economic value of copyrighted material for AI development, there is growing pressure to establish new systems of value-sharing between creators and AI developers.

One potential model involves licensing marketplaces that facilitate the legal use of copyrighted works for AI training. These platforms would allow authors, publishers, and rights holders to register content and set licensing terms, while AI companies could access the content in compliance with negotiated agreements. Similar to ASCAP or BMI in the music industry, such systems could create a scalable framework for balancing access and remuneration.

Another possibility is micro-royalty systems that track usage at the data-token or prompt level, though this approach presents significant technical challenges. Nevertheless, the underlying principle remains the same: creators should be compensated when their content materially contributes to the development or functionality of commercial AI systems.

Some AI companies are already beginning to adopt this model voluntarily. OpenAI, for instance, has signed licensing agreements with publishers like the Associated Press and Axel Springer. While Meta has not yet announced similar deals for LLaMA, it may face increasing pressure to formalize its approach to training data as commercial applications of its models expand.

Cultural and Normative Shifts: Balancing Progress and Protection

Finally, the implications of this case extend beyond the legal and economic domains into the cultural sphere. The ruling symbolizes a broader societal struggle to define the boundaries of ownership, originality, and authorship in the digital age. As AI-generated content becomes more prevalent in literature, journalism, art, and music, public attitudes toward creative labor and synthetic output are evolving.

Many observers argue that failing to protect creators will erode the financial and moral incentives to produce original work. Others counter that democratizing access to knowledge and creative expression through AI can unleash untapped potential and drive social and economic progress. This tension will not be resolved through legal doctrine alone; it will require sustained dialogue among technologists, artists, legislators, and the general public.

One possible outcome is the emergence of AI ethics standards and certification regimes—voluntary guidelines that promote responsible AI training practices, including respect for creator rights and data transparency. These frameworks could serve as interim solutions while lawmakers catch up with technological change.

What’s Next: Outlook & Best Practices

The dismissal of the copyright lawsuit against Meta marks a pivotal, yet incomplete, moment in the legal reckoning between generative AI and intellectual property. While Meta emerged procedurally victorious, the substance of the underlying legal and ethical questions remains unresolved. What happens next depends not only on future court challenges but also on the proactive measures taken by developers, creators, and policymakers to shape a fair and sustainable ecosystem for AI innovation.

Anticipating Future Litigation

Although the court declined to evaluate whether Meta's AI model training practices constituted copyright infringement, it did not foreclose future lawsuits that might be more narrowly tailored and evidentially robust. In fact, the judge’s reasoning implicitly signaled that similar cases could move forward if plaintiffs provide:

- Detailed evidence of ingestion and regurgitation of copyrighted material;

- Demonstrable market harm, such as economic substitution or licensing displacement;

- Clear identification of infringing outputs linked to specific inputs.

As such, the legal landscape is likely to see continued waves of copyright litigation involving other AI developers, particularly those whose models demonstrate higher output fidelity to source texts. The Silverman v. OpenAI and Getty Images v. Stability AI lawsuits remain active and may test different aspects of fair use and reproduction.

We can also expect new categories of plaintiffs, including visual artists, musicians, academic publishers, and content aggregators, to initiate similar proceedings. These cases may benefit from enhanced technical tools such as model auditing, watermarking, and token-level traceability, which make it easier to trace the use and reproduction of copyrighted works in AI-generated outputs.

Best Practices for AI Developers

The Meta case offers valuable lessons for AI developers looking to mitigate legal risk while continuing to innovate. Although the ruling favored Meta, it highlighted the increasing scrutiny facing large-scale data collection practices. To stay ahead of regulatory and judicial developments, AI developers should consider the following best practices:

- Data transparency: Maintain detailed records of training data sources, acquisition methods, and licensing terms.

- Avoid known copyrighted corpora: Exclude highly sensitive datasets (e.g., pirated books, proprietary media) unless rights are clearly granted.

- Implement model filters: Use guardrails to prevent models from reproducing long verbatim passages of copyrighted content.

- Engage with licensing frameworks: Where feasible, negotiate content use through emerging data licensing platforms or consortia.

- Collaborate with rights holders: Establish dialogue with publishers, authors’ associations, and visual content providers to explore voluntary agreements.

These actions can not only reduce legal exposure but also contribute to reputational credibility and long-term market trust.

Best Practices for Authors and Content Creators

For authors and creators, the Meta ruling underscores the importance of evolving legal strategies and technological awareness. It is no longer sufficient to rely on general claims of misappropriation; creators must build fact-based cases with measurable economic impacts. To that end, the following strategies are advisable:

- Monitor AI outputs: Use tools that detect potential reuse or paraphrasing of original works in generative outputs.

- Document economic losses: Track declines in licensing revenue, sales, or publishing interest where AI-generated content may be displacing demand.

- Participate in class actions: Collaborate with legal organizations and creative unions to strengthen collective bargaining and litigation power.

- Opt out where possible: Use opt-out mechanisms for web scraping or dataset inclusion (e.g., robots.txt, DoNotTrain metadata), and advocate for stronger enforcement of these protocols.

- Engage with policymakers: Participate in public consultations, surveys, and hearings to ensure creator perspectives shape emerging legislation and regulatory policy.

While the current legal climate may seem unfavorable, these proactive steps can help position creators as informed stakeholders rather than passive litigants.

Regulatory Outlook and Market Adaptation

Legislative and regulatory developments will play a decisive role in shaping the contours of AI training rights over the coming years. As of now, the U.S. remains reliant on judicial precedent and agency guidance from the Copyright Office and USPTO. However, momentum is building for:

- Mandatory transparency laws, requiring disclosure of training data sources;

- Collective licensing systems, modeled after those used in the music industry;

- Compulsory licensing schemes, where statutory rules govern permissible AI training with set royalty payments;

- International data governance alignment, particularly as the EU and UK adopt stricter transparency and opt-out requirements.

In the meantime, we are likely to witness a proliferation of private licensing deals between AI developers and rights holders. These agreements, while limited in scope today, may lay the groundwork for industry-wide standards if adopted broadly. The challenge lies in scaling these models to accommodate the vast and diverse range of content creators affected by generative AI systems.

Concluding Thoughts: Redefining the Balance

The Meta case may not have resolved the copyright challenges of generative AI, but it has clarified the nature of the debate. Courts are not dismissing the concerns of creators—they are demanding more precision in how those concerns are articulated and evidenced. This procedural rigor should be seen not as a barrier, but as an invitation: one that calls on both innovators and rights holders to participate in defining new norms.

The future of AI and creativity need not be adversarial. With transparent practices, equitable licensing models, and thoughtful policy development, it is possible to build a system where innovation and authorship reinforce each other. The law may be catching up slowly, but the conversation has undeniably begun.

References

- Meta Wins Lawsuit Over AI Use of Books – Bloomberg

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/meta-copyright-lawsuit-dismissed - Judge Tosses Authors’ Copyright Suit Against Meta – The Verge

https://www.theverge.com/meta-lawsuit-dismissal-copyright-llama - Meta Defeats Copyright Claim Over Book Data in AI Training – Reuters

https://www.reuters.com/legal/meta-wins-dismissal-copyright-suit-over-ai-2024 - Authors Slam Meta’s Use of Their Work for AI Training – Business Insider

https://www.businessinsider.com/meta-ai-books-lawsuit-dismissed-authors-response - Legal Experts Weigh In on Fair Use in AI Training – Wired

https://www.wired.com/story/meta-copyright-lawsuit-ai-fair-use - AI Training and the Future of Copyright – Financial Times

https://www.ft.com/content/meta-ai-copyright-lawsuit-analysis - Judge Chhabria’s Ruling: What It Means for Creators – TechCrunch

https://techcrunch.com/meta-ai-copyright-case-dismissed - Understanding Fair Use in the AI Age – Electronic Frontier Foundation

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/fair-use-training-ai - Anthropic and OpenAI Also Face Copyright Claims – Ars Technica

https://arstechnica.com/meta-anthropic-openai-copyright-lawsuits - US Copyright Office Statement on AI and Rights – Copyright.gov

https://www.copyright.gov/ai