Deepfake Politics: How AI-Generated Videos Are Threatening Democracy Worldwide

In recent years, artificial intelligence has made it possible to create convincingly realistic fake videos of public figures. These AI-generated fake political videos – often called deepfakes – can depict politicians and leaders saying or doing things that never actually happened. What began as a fringe internet novelty has rapidly evolved into a serious global concern for democracies, journalists, and policymakers. Deepfakes leverage powerful generative AI algorithms to produce fabricated video and audio that can be difficult for viewers to distinguish from real footage. As this technology becomes more accessible, incidents of fake political videos have surged worldwide, raising alarms about their potential to spread misinformation, disrupt elections, and erode public trust in media.

This comprehensive overview explores what deepfake political videos are and how they are made, surveys notable incidents and trends across different regions, examines the risks they pose to democratic societies, reviews the current state of detection technology and regulatory responses, and finally offers recommendations for mitigation and a look ahead to the future. By understanding the scope and scale of the problem – from a fake “Zelenskyy” urging Ukrainians to surrender to AI-generated “news anchors” spreading propaganda – we can better prepare to confront the growing threat of AI-driven political deception.

Understanding Deepfakes and AI-Generated Political Videos

To grasp the issue, one must first understand what deepfakes are and how they work. Deepfake is a portmanteau of “deep learning” and “fake”, referring to synthetic media created using AI algorithms. In essence, deepfakes use advanced machine-learning models – often generative adversarial networks (GANs) or similar techniques – to manipulate or fabricate video and audio content. By training on many images or recordings of a target person, a deepfake model can generate a highly realistic video in which that person’s face and voice are superimposed onto an actor’s performance, making it appear that the target said or did something they never did.

In the context of politics, AI-generated fake political videos typically involve a public figure (such as a head of state, candidate, or government official) depicted in a fabricated scenario. For example, an AI might produce a video of a president announcing a fake policy, or a candidate uttering inflammatory remarks – all without that person’s involvement. These videos can be very realistic: modern deepfakes capture subtle facial expressions, sync mouth movements to speech, and mimic vocal tone with alarming accuracy. Indeed, the technology has advanced to the point that many viewers “can’t discern deepfakes from authentic videos”.

How are deepfakes created? Initially, deepfake techniques emerged around 2017, when hobbyists began using open-source AI tools to swap celebrity faces into videos. Early deepfakes often exhibited glitches – flickering imagery, unnatural eye blinking, or imperfect lip-sync – but they have rapidly improved. Today’s methods use deep neural networks to map one person’s face onto another’s body in video, or to fully generate a synthetic face from scratch. For video deepfakes, an AI model may be trained on hours of real footage of a politician to learn their facial movements. Another AI model generates new frames blending an actor’s performance with the target’s face. Similarly, AI voice cloning can simulate the target’s voice to provide matching audio. The result is a fabricated video that, at a glance, looks authentic. Crucially, unlike traditional video editing (e.g. splicing or obvious doctoring), deepfakes leverage AI to produce seamless forgeries that can be very difficult to detect with the naked eye.

It’s important to distinguish deepfakes from simpler doctored videos sometimes called “cheap fakes” or “shallow fakes.” Not all fake videos rely on sophisticated AI. For instance, a widely publicized 2019 clip of U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi was merely a doctored video – slowed down to falsely make her speech seem slurred. That clip went viral and was viewed millions of times, highlighting the threat of video misinformation even without AI. Deepfakes take this a step further: using AI, an actor could literally put words in a politician’s mouth. A deepfake of Pelosi, for example, could realistically manufacture footage of her saying phrases she never said, rather than just manipulating existing footage. The consequences of such AI-driven deception are potentially far more disruptive. As one expert summarized: “Misinformation through altered videos is a rising concern… AI is now being used to produce clips that look genuine and realistically appear to show people saying words they have not spoken.”

Why are political deepfakes a concern? Politics relies heavily on public perception and trust. Video and audio recordings of leaders carry weight – they are often treated as compelling evidence of a person’s statements or intent. If that evidence can be faked, the door opens to powerful disinformation. A well-timed fake video of a candidate could swing voters; a fake statement by a president could spark international conflict or panic. Moreover, even the existence of deepfakes creates an effect called the “liar’s dividend”: people may start doubting real evidence, dismissing legitimate videos as “probably a deepfake.” In authoritarian settings, leaders have already used this defense to discredit real footage of wrongdoing. Thus, deepfakes threaten to undermine our shared sense of reality. In the words of one U.S. senator, deepfakes could become “the modern equivalent of ‘Don’t believe your lying eyes’,” eroding the basic trust needed for a functioning democracy.

In summary, AI-generated fake videos represent a new form of synthetic media with unique capabilities to deceive. They are made possible by recent advances in generative AI and have quickly moved from obscurity into mainstream awareness. Next, we will explore how this phenomenon is playing out around the world – through notable incidents and emerging trends.

A Global Surge: Notable Incidents and Trends

What was once experimental technology is now proliferating across the globe. In the past few years, political deepfakes have surfaced in various countries, serving as stark examples of both the technology’s reach and its risks. This section highlights some of the most notable incidents and trends worldwide, from election interference attempts and propaganda operations to politicians themselves harnessing AI for campaigns. Alongside these cases, the sheer growth in the volume of deepfake content underscores why this is a growing concern.

The United States and Western Democracies: In the U.S., fears of deepfakes influencing elections grew after a few high-profile early examples. In 2018, filmmakers created a viral deepfake of President Barack Obama (voiced by comedian Jordan Peele) to warn about the technology’s misuse. By 2019, the altered Pelosi video (though not a true deepfake) had already demonstrated how quickly misinformation could spread. In 2020, as the presidential race heated up, experts sounded alarms that fabricated videos could be weaponized against candidates. Thankfully, no major deepfake “October surprise” materialized that year, but by 2023 the landscape had shifted. Cheap and easy tools enabled “thousands [of deepfake videos] surfacing on social media, blurring fact and fiction in the polarized world of U.S. politics.”

Indeed, heading into the 2024 election, numerous deepfakes circulated online featuring American political figures. Some were blatantly satirical, but others aimed to mislead. For example, fake videos appeared of President Joe Biden making derogatory remarks and of Hillary Clinton endorsing a rival – none of which actually happened. Both went viral before being debunked, illustrating how “reality is up for grabs” in the digital campaign battlefield. Social media users shared an estimated 500,000 deepfake videos and audio clips on global platforms in 2023 alone, many of them political in nature. Even official political actors are now using AI: the Republican National Committee released an attack ad in April 2023 that used AI-generated imagery to depict a hypothetical future scenario. And in one case, a fake “robocall” audio of Biden circulated, exemplifying new forms of AI-enabled political dirty tricks. Western Europe has likewise seen incidents – for instance, in mid-2022 the mayors of Berlin, Vienna, and Madrid were tricked into video calls with someone impersonating Kyiv’s mayor Vitali Klitschko via deepfake, until the ruse became evident. These incidents, while contained, raised awareness in Europe about the threat of AI-driven political deception.

Conflict and Propaganda: The Ukraine War Example: One of the clearest illustrations of deepfakes’ dangerous potential occurred in March 2022, amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. A fabricated video of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy appeared online in which he seemingly urged Ukrainian troops to lay down their arms and surrender. The video was briefly inserted into a Ukrainian news website via hackers and even broadcast as a ticker on TV, before Ukrainian officials and media quickly denounced it as fake. The deepfake was not particularly advanced – Zelenskyy’s voice and accent were unconvincing and his head seemed unnaturally detached upon close inspection – but if it had been more polished, it might have sowed chaos. Experts noted that this was the first notable deepfake in warfare, likely intended as part of Russia’s disinformation campaigns, and warned it could be “just the tip of the iceberg”. Zelenskyy himself swiftly posted a real video message reassuring citizens that any surrender video was a fake, underlining the importance of rapid debunking in such scenarios. The “fake Zelenskyy” incident demonstrated how deepfakes can be weaponized as propaganda in conflicts, potentially undermining morale or spreading confusion. It also highlighted a global dimension: on Russian social media, the fake video spread widely even as Western platforms removed it.

Authoritarian States and State-Aligned Actors: Beyond one-off incidents, there is evidence that state actors and their proxies are experimenting with AI-generated video for influence operations. A striking case emerged in early 2023: a network of pro-Chinese social media accounts was found posting videos featuring AI-generated “news anchors” – fictitious English-speaking reporters with realistic faces – delivering propaganda messages favorable to Beijing. These deepfake news presenters (nicknamed “Wolf News” after a fake outlet branding) were created using a commercial AI video service and “almost certainly” were not real humans. In one clip, the avatar accused the U.S. of hypocrisy on gun violence; in another, it extolled China–U.S. cooperation. The videos were low-quality and garnered little engagement (often just a few hundred views), suggesting limited impact. However, analysts saw this as a proof of concept – a new tool in the disinformation arsenal. Graphika, a social media analytics firm, noted it was the first known instance of deepfakes being used in a state-aligned influence campaign. Similarly, reports have suggested that Russia has looked into using deepfake techniques for propaganda, given that “countries including Russia and China are already leveraging similar technology” in information operations. These developments show that AI-generated political content is not only the domain of pranksters, but is being actively explored by governments and their agents to sway public opinion at home and abroad.

Asia and Other Regions: The deepfake phenomenon is truly global. In India, for example, political strategists have used deepfakes in election campaigning – not to smear opponents, but to reach voters in multiple languages. Notably, during the 2020 Delhi assembly elections, a candidate from the BJP party released deepfake videos of himself giving the same speech in different languages (Hindi and Haryanvi), expanding his outreach to diverse linguistic groups. While this was a declared use of AI (the campaign admitted using the technology), it raised ethical questions and concerns that such tactics could be misused in less benign ways. By 2023, with general elections looming, India saw an even greater uptick in deepfake usage: one investigative report found politicians in India using “millions of deepfakes” to campaign, including AI-generated WhatsApp videos where candidates appear to speak local dialects they actually don’t know. This trend in India offers a glimpse of how AI can be wielded in politics – potentially as a positive tool for outreach, but also a Pandora’s box if malicious deepfakes enter the fray.

In the Middle East and Africa, awareness of deepfakes is also growing, sometimes spurred by rumors and scares. In 2019, Gabon’s government released a video of President Ali Bongo to dispel rumors about his health – but the video itself was so odd (with Bongo appearing stiff and unnatural) that opposition figures speculated it was a deepfake. This incident contributed to a climate of uncertainty that preceded an attempted coup in Gabon. Although it remains unproven whether the Bongo video was actually AI-generated or just poorly produced, the mere belief that a deepfake was used by those in power had real destabilizing effects. It underscored the “liar’s dividend” problem: once people know deepfakes exist, they may start suspecting any implausible or strange video of being fake – even if it isn’t. In Latin America, reported cases of political deepfakes have been fewer so far, but officials are on alert. For instance, during Brazil’s 2022 elections, observers warned that deepfakes could be employed to spread false statements by candidates, and Brazilian courts preemptively banned sharing certain manipulated media. As generative AI tools become globally available, experts note that no region is immune – the next election in any country could be the first to feature a damaging deepfake incident.

Deepfakes on the Rise

Accompanying these individual stories is a dramatic rise in the overall volume of deepfake content worldwide. While many deepfakes circulating online have nothing to do with politics (research consistently finds that the vast majority are non-consensual pornography or entertainment clips), the techniques used can easily be repurposed for political ends. The growth trajectory of deepfakes in general thus provides context for the expanding threat surface of fake political videos.

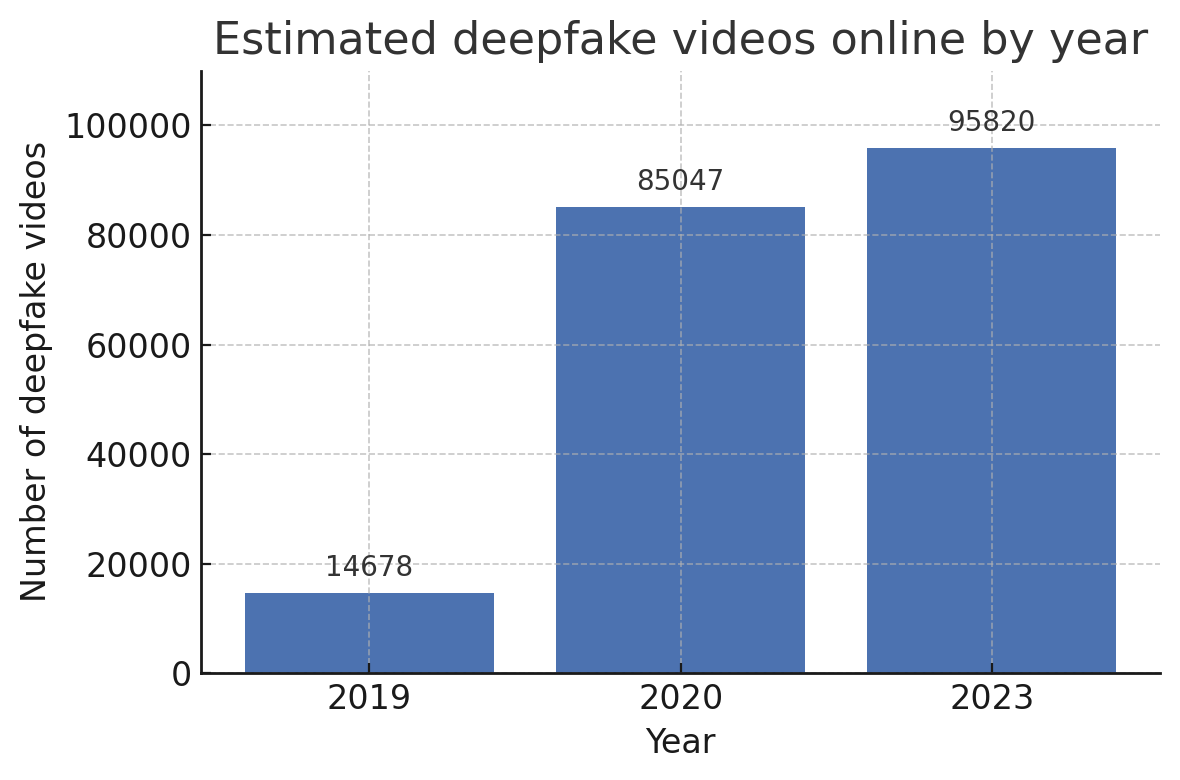

The proliferation has been explosive – from a few thousand in 2018 to tens of thousands by 2019, and around 95,000+ by 2023.

In 2018, there were only an estimated 7,000–8,000 deepfake videos detectable on the internet. By 2019 that number had roughly doubled to 14,678 known deepfake videos. The advent of easy-to-use apps and open-source GAN models then led to an explosion: researchers documented about 49,000 deepfake videos by mid-2020, which climbed to 85,000 by the end of 2020. In other words, the volume was doubling roughly every six months at that time. Growth has since continued. By late 2023, analyses showed around 95,000 deepfake videos in circulation online – a 550% increase since 2019. (It’s worth noting that ~98% of these were deepfake pornography, not political content. However, even a small percentage of 95,000 can include hundreds of political deepfakes, and the techniques overlap.) Another estimate focusing on social media predicted that about half a million deepfake videos and audio clips were shared on social networks in 2023 alone – indicating wide dissemination.

The lowering barrier to entry drives this surge. What once required AI expertise can now be done with off-the-shelf deepfake apps or cloud services. Generative AI tools have become more user-friendly and affordable: for example, cloning a voice that might have cost $10,000 in compute resources a few years ago can now be done for a few dollars via online APIs. There are even commercial deepfake studios where customers can rent an AI avatar or have a video fabricated for a fee. This democratization means political operatives, activists, or mischief-makers with minimal technical skill can potentially create fake videos. The global trend is clear – deepfakes are on the rise, and political deepfakes are riding that wave.

Threats to Democracy and Society

The rapid spread of AI-generated fake political videos poses multifaceted risks. At their core, deepfakes threaten to undermine the integrity of information, which is a foundation of democratic society. If seeing is no longer believing, the consequences can be far-reaching – from manipulating election outcomes and damaging public trust, to inciting social discord or even diplomatic crises. In this section, we examine the key risks and consequences associated with political deepfakes: how they can disrupt elections, erode citizens’ trust in media and institutions, enable new forms of propaganda and harassment, and create a climate of uncertainty that bad actors can exploit.

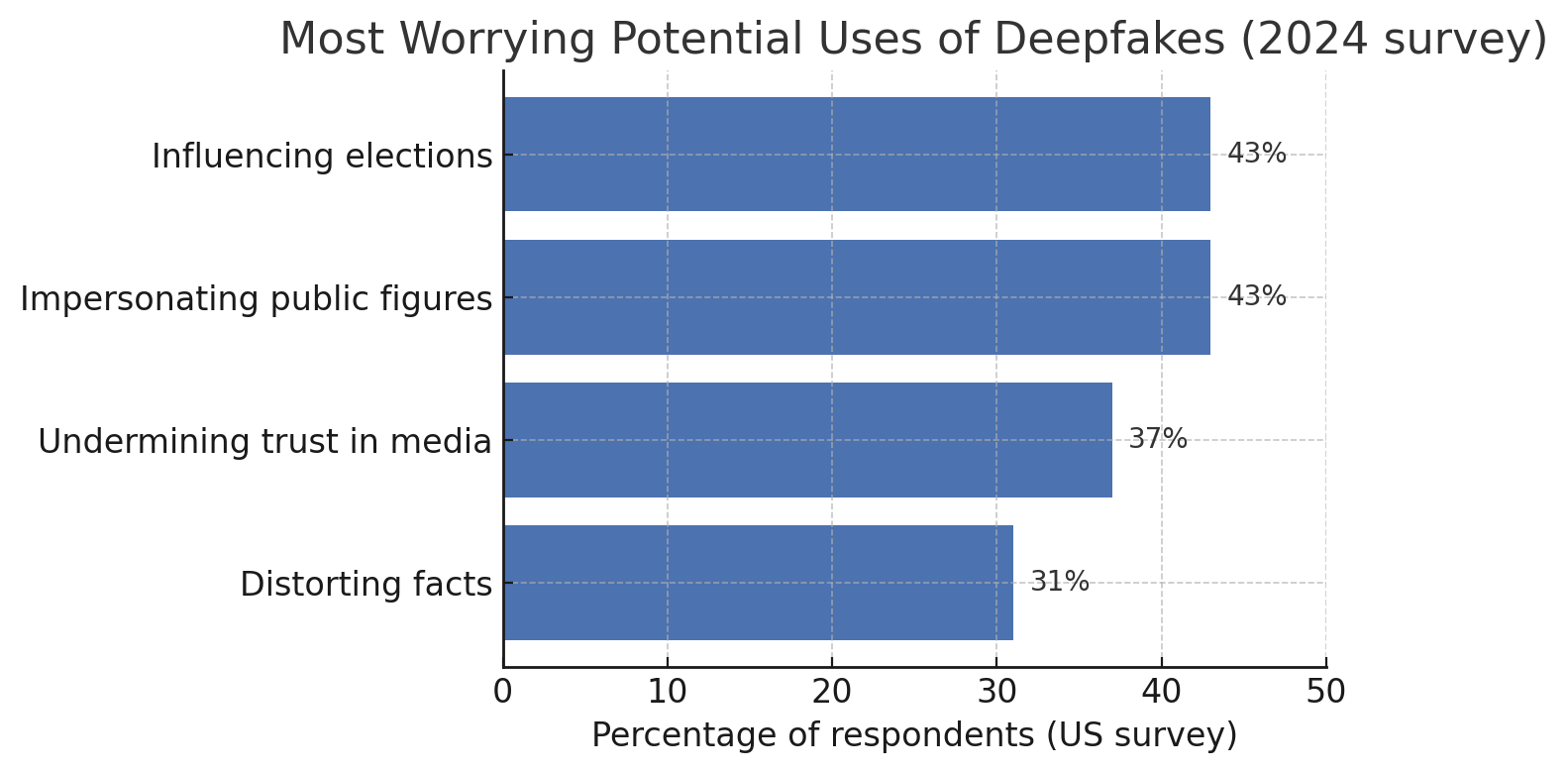

Election Interference and Manipulation: Perhaps the most frequently cited concern is that deepfakes could be used to influence elections unduly. In a democracy, voters rely on information (news reports, debates, candidate statements) to make decisions. A well-timed deepfake could inject false information into the public sphere at a critical moment. For instance, a fake video released on the eve of an election might show a candidate making racist comments or confessing to a crime – potentially swinging undecided voters or discouraging turnout. Even if debunked, the damage might be done, as retractions never spread as fast as the initial sensational lie. Nearly half of Americans (43%) in one survey said “influencing elections” was the most worrisome potential use of deepfakes. This was the top concern, tied with impersonating public figures. The fear is not theoretical: we have already seen minor attempts. In 2021, a deepfake video purported to show a mayoral candidate in another country accepting a bribe (it was quickly exposed, but not before rumors spread). The U.S. Director of National Intelligence has warned that foreign adversaries could deploy deepfakes in future campaigns to spread disinformation about candidates.

Even without a high-profile successful deepfake attack to date, the chilling effect on truth is palpable. In a McAfee survey, 43% of Americans said they were worried about deepfakes “altering the outcome of elections”. Election officials now must consider contingency plans for fake media. In 2020, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security even ran a war-game scenario of a fake video of a candidate to see how agencies might respond. The mere possibility makes campaigning more complicated – imagine candidates having to deny events that never happened (“No, I did not call for surrender; that video is fake”). This flips the usual burden of proof and could overwhelm the media’s ability to fact-check in real time. The integrity of elections depends on a shared reality; deepfakes directly attack that.

Erosion of Public Trust: Another profound consequence is the undermining of trust in media and institutions. Democracies require that citizens trust what they see and hear from leaders to some extent. Deepfakes make it difficult to do so. If any video might be fake, people could start dismissing legitimate news as fabrication. This is already occurring – when confronted with uncomfortable video evidence, politicians have begun to claim it’s a deepfake. For example, in 2020 a politician in Brazil preemptively asserted that a leaked compromising video of him was likely AI-generated (in fact, it was real). As deepfakes become more notorious, public skepticism grows. A Pew Research study found 63% of U.S. adults feel altered videos and images create confusion about the facts of current events. Similarly, 32% say they are now more suspicious of what they see on social media because of deepfakes. This general doubt can be healthy in small doses (critical thinking is good), but at scale it can lead to cynicism and relativism – people may throw up their hands and say “you can’t trust anything anymore.”

Such cynicism is dangerous. It can foster apathy (“why vote or engage if everything’s fake?”) and make citizens vulnerable to manipulation (“only our channel tells the truth, others spread deepfakes”). Authoritarian regimes thrive on undermining the concept of objective truth; deepfakes provide them a handy tool. As evidence of this erosion: 37% of Americans said their top concern about deepfakes is that they “undermine public trust in media”, second only to election interference. And in another poll, 61% believed that the average person cannot tell what videos or images are real anymore. When majorities of the public doubt the authenticity of what they see, the societal consensus on reality frays. This “truth decay” can polarize communities, as each faction believes only the narratives it wants to believe. The result is a fragmented information environment – fertile ground for conspiracy theories and disinformation.

What potential uses of deepfakes worry Americans the most? A 2024 survey highlights election interference (43%) and impersonation of public figures (43%) as top concerns, followed by undermining trust in media (37%) and distorting facts or history (31%).

The “Liar’s Dividend” and Political Accountability: Paradoxically, while deepfakes can incriminate the innocent, they can also protect the guilty by providing plausible deniability. This is the concept known as the liar’s dividend. Essentially, when people know that very realistic fake videos can be made, a dishonest politician caught in an authentic scandal can claim the incriminating video or audio is a deepfake – and some segment of the public might believe it. This has troubling implications for accountability. For example, suppose clear video evidence emerges of a candidate engaging in corruption. In the past, that might have ended their career. Today, that candidate might insist “it’s a deepfake, my enemies faked it,” exploiting partisan divides to avoid consequences. Without forensic expertise, many citizens wouldn’t be sure what to believe. Thus deepfakes could enable corrupt officials to escape justice by seeding doubt about real evidence. This dynamic has already played out: in 2019, when a compromising video of a government official in Malaysia leaked, some supporters claimed it was AI-generated to discredit it (despite no strong evidence of that). As deepfakes get more advanced, such tactics will become more common. The net effect is a degradation of accountability – video proof is no longer the gold standard it once was.

Psychological and Social Impact: Beyond the tactical harms, there is a broader psychological impact on society. Being bombarded with hyper-realistic falsehoods can cause “reality apathy” – a sense of fatigue and inability to discern truth, leading people to disengage. Researchers have found that even exposure to deepfakes can make people more unsure about legitimate media. Over time, a population inundated with AI fakes might develop a blanket distrust of all news, or conversely, an indifference to being lied to (“everything’s fake anyway, so what does it matter”). Both outcomes are harmful to democratic discourse. Misinformation can also entrench polarization: people tend to believe deepfakes that align with their biases and dismiss ones that challenge their views, reinforcing echo chambers. For example, a partisan might readily accept a deepfake of an opposing politician behaving badly, but cry foul at one of their favored politician. This selective belief exacerbates divisions.

There are also harassment and personal reputation risks. Politicians, journalists, and activists could be targeted by deepfakes designed to humiliate or discredit them. Consider a fake video of a female journalist in a compromising situation – even if fake, it could subject her to harassment or undermine her credibility. (This intersects with the epidemic of deepfake pornography, where women’s faces are mapped onto explicit videos – often used as a tool of revenge or intimidation. A female political candidate could similarly be targeted to derail her campaign.) The threat of being deepfaked itself might intimidate people from public service or speaking out.

National Security and International Stability: At a state level, deepfakes can pose national security risks. Intelligence agencies warn that fake videos of world leaders could be used to stoke international conflict or diplomatic incidents. Imagine a deepfake of a country’s president declaring war or insulting a foreign ally – even a short delay in debunking it could set dangerous events in motion (troop movements, market crashes, etc.). Military personnel and diplomats now have to consider that videos or audio purportedly from their counterparts might be fabrications intended to deceive. In 2020, militants in the Middle East reportedly circulated a deepfake audio message impersonating a senior leader to confuse enemy forces – a rudimentary but telling example of what could come. U.S. Senators Marco Rubio and Mark Warner have both cited scenarios where deepfakes might trigger false alarms in crises, calling it a new kind of cybersecurity threat.

In summary, the consequences of AI-generated fake political videos strike at the heart of democratic society: free and fair elections, informed citizenry, trust in journalism, and accountability of leaders. The public is increasingly aware of these stakes – over three-quarters (77%) of Americans say there should be stricter regulations and restrictions against misleading deepfakes. And nearly 7 in 10 people globally report increased concern about deepfake impacts compared to a year ago. As the technology improves, these risks become more pronounced. However, it’s not all doom and gloom: in the next section we examine how researchers, tech companies, and governments are fighting back, and what measures are being implemented to mitigate the threat.

Detection Efforts and Policy Responses

Confronting the challenge of deepfakes requires a multipronged approach. On one front, technologists are racing to develop detection tools that can identify AI-manipulated media. On another front, policymakers and regulators around the world are crafting laws and guidelines to curb malicious use of deepfakes and to hold perpetrators accountable. Social media platforms are also implementing policies to limit the spread of deceptive synthetic media. This section provides an overview of these responses – both the promise and limitations of detection technology, and the emerging regulatory landscape across different jurisdictions.

The Arms Race in Detection Technology

Detecting deepfakes is, unfortunately, as challenging as creating them – if not more so. As one digital forensics expert, Hany Farid, starkly put it, “we are outgunned… the number of people working on the video-synthesis side, as opposed to the detector side, is 100 to 1.” The problem is essentially an AI arms race: every time detectors learn to spot certain artifacts or inconsistencies in fake videos, creators can improve their algorithms to evade those checks. Nonetheless, significant efforts are underway to equip journalists, platforms, and the public with tools to tell real from fake.

Current Detection Techniques: Early deepfake detection algorithms often looked for visual quirks. For example, some deepfakes didn’t blink normally or had irregular eye movements – a giveaway exploited by one detector tool (until deepfake creators trained their models to blink naturally). Other detectors analyze pixel-level artifacts, compression noise, or inconsistencies in lighting and shadows on a person’s face. More advanced methods use “soft biometric” analysis: they examine the facial movements or speech patterns of an individual and see if they match the known natural behavior of that person. For instance, each person has unique ways they move their mouth or gesture when speaking; an AI can be trained on genuine footage of a politician and then flag if a new video deviates in hundreds of subtle ways that a deepfake might accidentally introduce. Researchers have also explored using signals like heart rate – surprisingly, an algorithm can sometimes detect the pulse of a person in a video by analyzing skin color fluctuations; a deepfake might lack a realistic pulse signal.

On the audio side, detectors look at spectrograms of speech for glitches or signs of splicing. There are also AI models trained to discern authentic vs. synthesized voices. Some promising research even uses blockchain-like verification, where cameras or software sign digital footage at the source, so any tampering can be later detected by verifying the signature.

Effectiveness and Limitations: While many detection techniques show success in lab settings, real-world performance is mixed. Studies have found that human eyes are only about 57% accurate at identifying deepfake videos – essentially no better than chance. AI detectors can reach higher accuracy (some claim 80–90% on benchmark data sets). However, those rates often drop when facing novel deepfakes not seen in training. It’s a moving target; as generative models improve, the fakes become more “lifelike” and harder to spot. For instance, one recent test showed participants a mix of real and fake faces – nearly half could not correctly recognize a real vs fake face (a 48% success rate, barely above random guessing). Intriguingly, that study found people actually rated deepfake faces as looking more trustworthy than real ones on average – indicating how polished AI-generated media has become in fooling our perceptions.

Automated detectors also face an adaptation problem. Many current detectors are trained on specific generative techniques; if a new deepfake method comes along, the detector might miss it. It’s a classic cat-and-mouse scenario. For example, detectors that focused on face-swapping cues struggled when “full-body” deepfakes or lip-sync-only deepfakes appeared. Some experts fear we may be heading towards a point where extremely sophisticated deepfakes (built with multimodal AI and fine-tuning) are “indistinguishable from real” to all existing detection approaches – a so-called deepfake singularity. So far, we’re not quite there, but we’re getting closer. As one researcher lamented, “It’s always going to be easier to create a fake than to detect a fake.”

That said, detection is improving too. Tech giants and academic consortia have invested in this challenge. In 2020, Facebook and partners ran a Deepfake Detection Challenge to crowdsource better algorithms, leading to some incremental advances. Companies like Microsoft have rolled out deepfake detection software (e.g. Microsoft Video Authenticator) for newsrooms and campaigns to use in verifying content. Startups are emerging that specialize in AI content authentication. There is also work on proactive measures: instead of trying to catch fakes after the fact, embed watermarks or fingerprints into AI-generated content at the time of creation. For example, OpenAI has experimented with adding hidden patterns in AI outputs (including images) that detectors can later pick up, although this is still at early stages and can often be circumvented.

Another approach being adopted is content provenance: initiatives like the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA) propose using cryptographic signatures on authentic videos at the source (e.g., by the camera or device that recorded it). This way, any subsequent alterations would break the signature. If widely implemented, consumers could have a way to verify that a video claiming to be from a reputable source (say CNN or a government press office) is exactly as originally produced. Adobe’s Content Authenticity Initiative is piloting similar technology for images and video, adding metadata that tracks editing history. In the future, your phone might automatically flag a video as “unverified source” versus “digitally signed by source” much like websites use HTTPS certificates.

In sum, no single silver bullet for detection exists yet, but a combination of AI-driven analysis, metadata authentication, and public awareness can mitigate the threat. A crucial element is also time – deepfakes intended to deceive often have the most impact in the immediate aftermath of release. Rapid detection and debunking by fact-checkers or authorities can limit harm. For example, the fake Zelenskyy surrender video was publicly debunked within hours by experts and even by Zelenskyy himself, sharply limiting its impact.

Recommendations and Future Outlook

As we’ve seen, AI-generated fake political videos present a serious challenge – but not an insurmountable one. Addressing this issue will require coordinated efforts across technology, policy, media, and education. In this concluding section, we outline key recommendations for various stakeholders to combat the threat of deepfakes, and then discuss the future outlook: how the deepfake landscape may evolve in the coming years and what hope we have of staying ahead of the curve.

1. Strengthen Detection and Verification Systems: Continued investment in deepfake detection R&D is vital. Governments and industry should fund research to improve AI detectors (perhaps through public competitions akin to cybersecurity “bug bounties”). Equally important is building verification infrastructure: implement content authentication standards (like C2PA) so that news organizations and official sources can digitally sign their videos. This would enable downstream viewers to verify authenticity. Camera manufacturers could explore adding hashes or watermarks at the point of capture. While detection alone won’t solve everything, it can raise the cost for deepfake perpetrators and reduce the window of credibility for fakes. A future goal should be that most reputable video content comes with a verifiable origin stamp, making it harder for fake clips to impersonate real ones.

2. Clear Labeling and Disclosure: Creators of AI-generated media, especially in political contexts, should label their content as AI-generated. This might be achieved through legal requirements (as the EU and China are doing) or voluntary ethical norms. For example, political campaigns and PACs could pledge not to use deepfakes to deceive – and to clearly mark any synthetic imagery or audio used in ads. Social media platforms can also auto-label detected deepfakes (e.g., “Warning: this video is suspected to be AI-altered”) to give viewers context. Some platforms already have started this, but consistency and coverage can improve. Ultimately, seeing an “AI-generated” label on a video of a politician would immediately signal skepticism to viewers.

3. Legal and Regulatory Action: Policymakers should close the gaps in current laws. This includes passing targeted statutes against harmful deepfakes (such as using a fake video to incite violence or to suppress voting) while carefully protecting satire and free expression. Election laws may need updating – for instance, requiring any election-related advertisement that uses synthetic media to carry a disclosure. Law enforcement and election commissions should also be trained in how to handle deepfake incidents (e.g., preserving evidence, tracing the source via digital footprints). Internationally, cooperation is key: countries could share best practices and even intelligence on deepfake operations originating from overseas. Given the cross-border nature of online disinformation, a treaty or at least bilateral agreements on not using deepfakes for malicious interference (though hard to enforce) might be worth pursuing, akin to agreements on cyber espionage or information warfare norms. At the very least, diplomats can bring up deepfake propaganda as an unacceptable behavior in international forums.

4. Platform Accountability and Tools: Social media and content platforms are the main distribution channels for viral deepfakes. They should continue to refine their content moderation to swiftly remove or context-label deceptive deepfakes that can cause harm. Platforms could integrate deepfake detection into the upload process – similar to how YouTube scans for copyrighted audio, they could scan videos for known deepfake signatures or use hashing to catch reuploads of known fakes. They should also provide users (especially high-risk targets like public figures) with tools to report suspected deepfakes and get expedited review. Another idea is user education prompts: if someone is about to share a video that has been flagged as a possible deepfake, the platform might show an alert like “This video might be manipulated. Are you sure you want to share?” which can reduce casual spread. Collaboration between platforms is also beneficial – an information sharing hub for deepfake incidents (like how cybersecurity firms share threat intel) could help ensure a fake busted on one network doesn’t simply migrate to another.

5. Public Awareness and Media Literacy: Perhaps the most powerful long-term defense is an informed public. Citizens should be educated about the existence of deepfakes and how to approach media critically. This doesn’t mean instilling cynicism that “everything is fake” – rather, teaching verification habits: check multiple sources, be wary of videos that confirm your preconceived notions too perfectly, slow down before sharing shocking clips, and use fact-check resources. Educational institutions can include deepfake awareness in digital literacy curricula. Government agencies and NGOs might run public service campaigns akin to anti-scam or anti-rumor campaigns, showcasing examples of deepfakes and tips to spot them. Encouraging a culture of “trust but verify” for online media will reduce the impact of fake videos. Encouragingly, because of news coverage of deepfakes, people are becoming more aware; one study noted global efforts to warn people have made them more suspicious of deepfakes (which, in moderation, helps). Nearly 70% of people say their concern about deepfakes has increased in the past year. Harnessing that awareness into constructive skepticism is key.

6. Support for Victims and Targets: We should also consider those who are directly harmed by deepfakes – whether a public figure defamed by a fake video, or an average citizen whose image is misused. Legal systems should ensure there are avenues for redress (e.g., the ability to quickly get a court injunction to remove a deepfake or sue for damages after the fact). Counseling or protection might be needed in cases where deepfakes provoke threats (for example, a politician who is deepfaked into a hate speech might receive real harassment or worse). By treating deepfake incidents as a serious form of cybercrime or abuse, authorities can better support victims.

The Road Ahead: Future Outlook

What does the future hold for AI-generated political videos? In the near term, we can expect deepfakes to become more sophisticated and harder to detect. Advancing AI models – including deep learning architectures and now diffusion models – are continually improving in generating realistic imagery. We may see real-time deepfakes, where a person’s face and voice are puppeted live on a video call (early versions of this exist). Such capability could be used, for example, to impersonate a world leader during a live press conference or a private diplomatic call, with profound implications if believed even briefly. The cost and skill required to make deepfakes will also continue to drop, which likely means an increase in volume: more low-grade deepfakes flooding social networks, and possibly more high-grade ones used in targeted ways.

On the flip side, detection will also improve, and importantly, society’s resilience to deepfakes will grow. Just as we adapted to the era of Photoshop by learning to doubt too-perfect magazine photos, we will adapt to the era of deepfakes by treating video evidence with a bit more caution and demanding corroboration. Journalists, for instance, are already instituting verification steps for user-submitted videos (checking shadows, metadata, consulting experts) – these practices will become standard operating procedure whenever a potentially game-changing video emerges. News organizations might routinely run authentication checks on politically sensitive footage. Voters, having heard of deepfakes, may be less prone to knee-jerk reactions and wait for confirmation. This public skepticism, while it carries the risk of undermining trust as noted, can be channeled positively: “don’t trust, verify” might become a mantra that helps inoculate the population against being easily duped.

It’s also possible that watermarking solutions will mature, meaning much AI-generated content might come with an identifier. For example, major AI model providers (like OpenAI, Google, etc.) could build in invisible watermarks in all outputs. If these become standard, any content from those models can later be flagged by a simple scanner. If a deepfake maker tries to remove the watermark, that usually degrades the quality, tipping off detectors in other ways. Alternatively, the arms race could escalate to a point where AI itself is used to verify authenticity – imagine deepfake detectors so advanced that they become akin to antivirus software on everyone’s device, constantly scanning and warning about dubious media.

In the policy realm, we are likely to see more laws catching up. By 2030, it would not be surprising if most democracies have enacted comprehensive frameworks around synthetic media. The EU’s AI Act will set a precedent; other countries may adopt similar rules requiring labeling or even licensing of certain AI tools. We may also witness landmark legal cases that clarify liabilities – for instance, a lawsuit against a deepfake creator that results in significant penalties could deter others, or a ruling that a platform is liable for not removing a deepfake might force stricter moderation.

However, one should not be naive – determined malicious actors will still attempt to exploit deepfakes, especially in environments with weak institutional checks. The hope is that by raising awareness and deploying countermeasures, any such attempts can be quickly exposed and neutralized. In a way, society needs to develop an immune response to this “pathogen” of disinformation. Each deepfake incident that is successfully debunked and mitigated strengthens the muscles of our collective defense, much like fighting off a virus builds immunity.

Finally, there is a broader positive potential: the very AI technology used for deepfakes can also be used for good in politics (e.g., dubbing speeches into multiple languages to make political communication more inclusive, as seen in India) or in art and education (creating historical figures’ likeness for a documentary). So, the goal is not to stifle innovation, but to ensure AI is used responsibly. With thoughtful policies and vigilant society, we can reap the benefits of generative AI while minimizing its dangers.

Conclusion: AI-generated fake political videos are indeed a growing concern – but by recognizing the threat early, democracies worldwide are better positioned to counter it. It will take vigilance: robust detection tools, smart laws, responsible tech industry behavior, and a discerning public. The global and regional perspectives discussed show that this is a shared challenge; no country is untouched, and lessons learned in one place can aid others. We stand at a critical juncture where trust in media and democracy itself may hinge on our response to this AI-driven deception. By acting decisively and collaboratively, we can shine a light on deepfakes and ensure that truth prevails over falsehood in the digital age.

References

- Spiralytics – “70 Key Deepfake Statistics” spiralytics.comspiralytics.com

- Reuters – Harrell, “Facebook CEO says delay in flagging fake Pelosi video was mistake” reuters.comreuters.com

- Reuters – Ulmer & Tong, “Deepfaking it: 2024 election collides with AI boom” reuters.comreuters.com

- NPR – Allyn, “A deepfake Zelenskyy video was ‘tip of the iceberg’” npr.orgnpr.org

- The Record – Antoniuk, “Deepfake news anchors spread Chinese propaganda” therecord.mediatherecord.media

- TV Tech – Winslow, “Survey: Deepfake concerns spike as election approaches” tvtechnology.comtvtechnology.com

- SecurityHero – “2023 State of Deepfakes: Key Findings” securityhero.iosecurityhero.io

- ScoreDetect Blog – “Deepfake Disclosure Laws: Global Approaches” scoredetect.comscoredetect.com

- Berkeley iSchool – citing Washington Post, “Top AI researchers race to detect deepfakes” ischool.berkeley.edu

- Pew Research – Duggan, “Distorted Facts, Deepfakes, and Confusion” spiralytics.comspiralytics.com

- McAfee/TVTechnology – “Deepfakes and Elections” survey summary tvtechnology.comtvtechnology.com

- Deeptrace Labs – “The State of Deepfakes” report spiralytics.com