ChatGPT Addiction and Withdrawal Symptoms: A New Digital Dependency

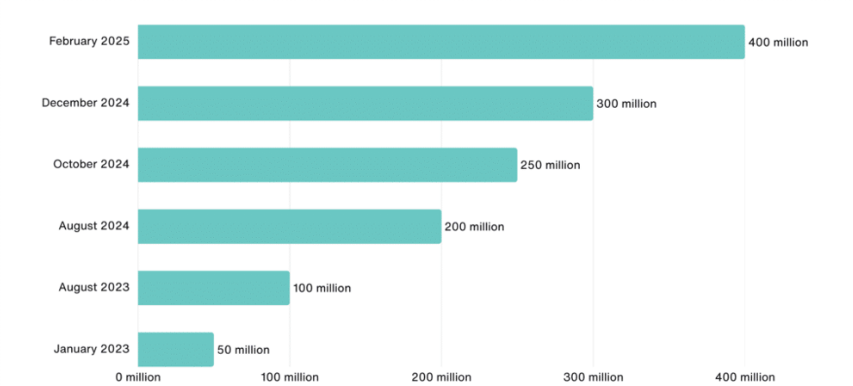

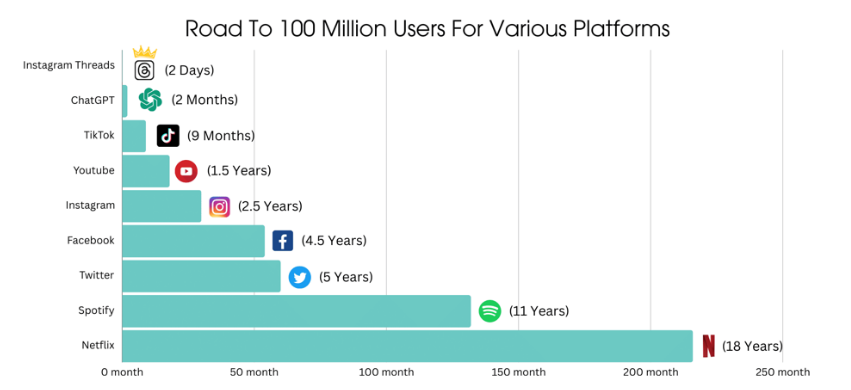

The rise of ChatGPT – an AI chatbot capable of human-like conversation and problem solving – has been meteoric. Within months of its late-2022 debut, ChatGPT amassed millions of users around the world, integrating into daily routines for work, study, and even companionship. Its utility and novelty have made it a global sensation. However, alongside the enthusiastic adoption, experts are observing an unsettling trend: some individuals report addictive behaviors in their use of ChatGPT. In early 2025, researchers at OpenAI and MIT noted that a subset of users were exhibiting early signs of addiction – including withdrawal-like symptoms, mood swings, and loss of control over usage. While the majority of users interact with ChatGPT in a healthy, task-oriented manner, these findings have raised red flags in the mental health and tech communities about the potential for ChatGPT dependency.

This detailed exploration examines what “ChatGPT addiction” means, how it might develop, and its parallels with other well-known technology-related addictions. We’ll delve into the psychological mechanisms (such as dopamine-driven reward loops, novelty-seeking, and parasocial interactions) that could make an AI chatbot compelling to the point of dependency. Withdrawal symptoms – the mental and emotional effects of reducing or stopping ChatGPT use – will be discussed, comparing them to those seen in internet and gaming addictions. Real-world case studies of individuals who felt “hooked” on AI chat will illustrate the human impact of this phenomenon. Finally, we consider strategies for managing or treating such digital dependence, from personal coping techniques to emerging professional and regulatory approaches.

ChatGPT addiction is not an official diagnosis, but as this article will show, it is a concept being taken increasingly seriously by researchers and clinicians. By examining the evidence and expert insights available so far, we aim to shed light on whether an AI chatbot really can become addictive – and if so, what users and professionals can do about it.

ChatGPT’s exploding user base (weekly active users in millions). Its unprecedented growth within just two years has raised questions about potential overuse and dependency.

What Is ChatGPT Addiction?

In clinical terms, “ChatGPT addiction” is not yet a formally recognized disorder – you won’t find it in diagnostic manuals. Rather, it’s a proposed phenomenon describing a pattern of compulsive, excessive use of ChatGPT (or similar AI chatbots) that begins to interfere with a person’s daily life and well-being. In essence, it falls under the umbrella of behavioral addictions (also called process addictions), where a behavior or activity becomes addictive in a way similar to substance abuse, absent any ingested drug. Over the past decades, mental health experts have applied this concept to things like video gaming, social media, online gambling, and internet use in general. Now, some are asking: should we consider compulsive chatbot use in the same light?

Researchers have begun to lay out what ChatGPT addiction might look like. In a 2025 viewpoint paper, Yankouskaya et al. describe how ChatGPT’s features (instant answers, personalized interaction, 24/7 availability) can foster dependency. The AI provides instant gratification and highly adaptive dialogue, potentially blurring the line between machine and human interaction. This can create “pseudosocial” bonds – one-sided relationships with the AI – that start to replace real human connection. At the same time, ChatGPT streamlines tasks and decision-making so effectively that users may come to over-rely on it for everyday decisions, eroding their own confidence and critical thinking. According to these researchers, such patterns align with known hallmarks of addiction – people building up tolerance, feeling conflict with life priorities, and showing compulsive use despite negative consequences.

It’s important to note there is debate in the academic community about labeling this “addiction.” Some psychologists urge caution against hasty new diagnoses. For instance, a forthcoming commentary in Addictive Behaviors pointedly asks if people are truly becoming “AIholics,” suggesting that the very construct of ChatGPT addiction might be premature or exaggerated (Ciudad-Fernández et al., 2025). These experts argue that not every intense new technology usage should be pathologized, and that we must differentiate between healthy enthusiasm and clinical addiction. Indeed, as of now most ChatGPT users do not engage with the AI in an emotionally dependent way, and “emotional interactions with ChatGPT are incredibly rare, even among heavy users” according to the MIT/OpenAI studies. In other words, the norm is to treat ChatGPT as a useful tool, not an object of addiction.

That said, history has shown that a small percentage of users can develop problematic use patterns with almost any engaging technology. Just as a minority of gamers develop gaming disorder, a minority of chatbot users might develop an unhealthy obsession. The concept of ChatGPT addiction refers to those extreme cases where usage becomes compulsive and starts to resemble an addiction in its psychological profile. Typically, this would entail: spending excessive time chatting with the AI (to the detriment of other activities), feeling unable to cut back, turning to the chatbot for emotional comfort or escape, and experiencing distress or dysfunction as a result.

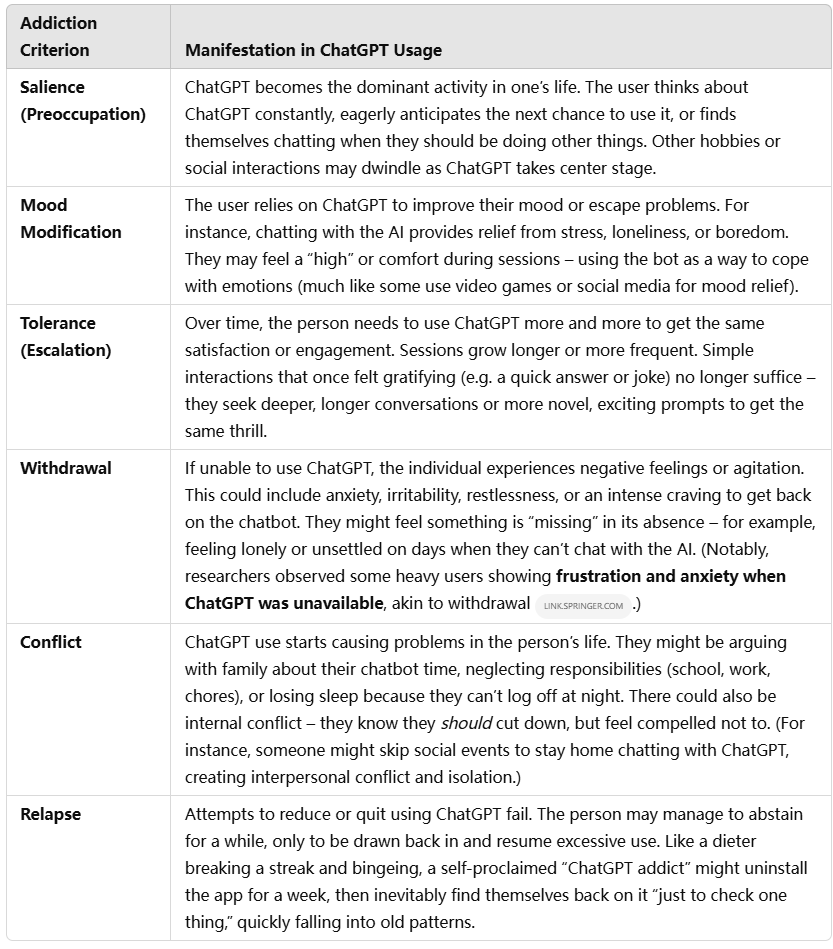

Behavioral Addiction Criteria Applied to ChatGPT

Psychologists have identified several core criteria that define behavioral addictions. Mark Griffiths’ well-known components model of addiction, for example, outlines consistent features seen in addictions ranging from gambling to gaming. Below is a summary of these criteria and how they might manifest in the context of ChatGPT use:

Not every case will tick all these boxes, but these criteria provide a framework for evaluating when heavy ChatGPT use crosses the line into maladaptive territory. The salience of ChatGPT in someone’s life and the presence of withdrawal symptoms are particularly telling signs of a dependency forming. Next, we explore why ChatGPT has the potential to meet these criteria – what makes this AI chatbot so engaging that it could become addictive.

Why ChatGPT Can Be Addictive: Psychological Mechanisms

Many people are perplexed by the idea that an AI chatbot could be addictive. After all, ChatGPT doesn’t deliver a chemical hit like a drug, nor is it a video game explicitly designed with points and levels. However, several psychological and neurobiological mechanisms known to contribute to addictive behaviors may also be at play when using ChatGPT. Here are some key factors that make ChatGPT so engaging – and potentially habit-forming:

- Dopamine and Instant Gratification: Interacting with ChatGPT can trigger the brain’s reward circuits. Humans are hard-wired to seek information and novel stimuli; getting an answer or an interesting response from the AI can be intrinsically rewarding. Each time ChatGPT satisfies a query or surprises the user with a clever answer, it provides a little burst of accomplishment or amusement. This positive reinforcement can release dopamine, the neurotransmitter heavily involved in pleasure and learning. Crucially, the rewards from ChatGPT are immediate and on-demand – there’s no waiting for a show to air or a friend to reply. This immediacy creates an instant gratification loop: you think of something, you get a result. In behavioral addiction terms, ChatGPT functions like a slot machine of information and ideas, ever-ready to deliver a payoff. In fact, studies of digital media suggest that unpredictable, intermittent rewards drive compulsive engagement – much like a gambler pulling a slot lever. With ChatGPT, you never know when it will produce an especially insightful answer or creative solution, and that unpredictability can hook the brain’s reward system.

- Novelty-Seeking and Endless Content: Unlike static websites or even social media feeds, ChatGPT can generate practically endless novel content tailored to the user’s prompts. Every answer is a little different; you can ask it to explain quantum physics one minute and role-play as a historical figure the next. This constant novelty is compelling for curious minds – there’s always something new to learn, a new angle to explore, or a new story it can create. Novel stimuli are known to activate dopamine as well; we are drawn to seek new information (an effect sometimes dubbed “information addiction” or infomania). ChatGPT is like an infinite library and creative studio in one. For some, this bottomless well of content can lead to spending far more time interacting than initially intended, as one question leads to another in a never-ending chain. The user may find it hard to stop because there’s always another idea – just one more prompt! – that comes to mind. This dynamic can foster a “one more hit” mentality analogous to how someone on YouTube might autoplay videos for hours, or a gamer might keep doing “one more quest.”

- Parasocial Relationships and Emotional Attachment: One especially intriguing (and concerning) mechanism is the formation of parasocial bonds with ChatGPT. Parasocial interaction refers to one-sided relationships people develop with media figures or characters – for example, feeling a personal connection to a favorite TV host or influencer who doesn’t actually know you. In the case of ChatGPT, which is designed to emulate conversational human style, users can start to feel like the AI is a friend, mentor, or confidant. The chatbot’s friendly tone, endless patience, and non-judgmental responses create an illusion of social interaction. Researchers note that AI chatbots can create a “sense of social presence,” fooling our minds (to a degree) into responding as if we’re in a real relationship. Crucially, this bond is pseudosocial – it feels like a relationship, but is one-sided and not truly reciprocal.For vulnerable individuals, it’s easy to anthropomorphize the AI and imbue it with emotional significance. A lonely or socially anxious person might begin to rely on ChatGPT for companionship and emotional support. Indeed, many young users report telling the bot about their problems, seeking comfort or advice when they have no one else to turn to. In one user’s words, “I am addicted to ChatGPT because it provides me a safe and non-judgmental environment… as a person who isn’t very social, talking with ChatGPT helps me manage stress and anxiety and feel less isolated, just like in the movie Her.”. This reference to the film Her (where a man falls in love with an AI assistant) underscores how real those feelings can become. The AI offers consistent, always-available positive interaction without the complexities of human relationships – no risk of rejection or conflict. According to social psychology, humans tend to favor relationships where the rewards outweigh the costs, and in an AI relationship the emotional “cost” is almost zero. The bot is always there on the user’s terms. Over time, a user may come to prefer the chatbot over real people, reinforcing isolation and dependence on the AI for emotional needs. This dual parasocial interaction (user to AI persona, and user to the helpful “information source”) is a novel aspect of ChatGPT use that can deepen engagement to potentially unhealthy levels.

- Cognitive Offloading and Dependency: Another mechanism is more about productivity and decision-making than emotion. ChatGPT is incredibly useful for outsourcing cognitive work – be it drafting emails, brainstorming ideas, coding, translating, you name it. It acts as a super-smart assistant. While this is a boon, it can also create a crutch. People might start leaning on ChatGPT for every little question or decision, from writing a school essay to choosing what to eat. Over-reliance can set in gradually: the more you delegate to the AI, the less you trust your own skills or effort. Psychologists refer to this as a form of automation bias and learned dependency. For example, if a student consistently uses ChatGPT to solve math problems or generate ideas instead of trying themselves, they may lose confidence in their own abilities. One concerning finding is that when heavy users suddenly don’t have the AI, they can experience “decision paralysis” or uncertainty. A study of AI in decision support found that people who frequently relied on AI recommendations felt anxious and unsure when those systems were unavailable, which the authors likened to withdrawal symptoms. In essence, the brain gets accustomed to the AI always being there as a cognitive aid, and its absence triggers distress. Users may come to feel they can’t function normally without it, which is a classic sign of dependency. Additionally, by always choosing the shortcut of asking ChatGPT, individuals may reinforce a habit loop that’s hard to break: why struggle through a tough problem or read a long article when the AI can summarize or answer it instantly? That convenience is seductive, and breaking away to work without the AI can induce discomfort or lowered motivation – much as a person used to GPS navigation might feel lost and anxious when forced to read a map.

- The Variable Reinforcement Loop: From a behavioral standpoint, ChatGPT use can engage a variable reinforcement schedule similar to social media or even gambling. Not every interaction is equally satisfying – sometimes ChatGPT gives a fantastic, insightful answer (high reward), other times it might give a dull or wrong answer (low reward). The user doesn’t know which it will be, but the potential for a great response keeps them coming back. This dynamic of unpredictable reward is known to strongly reinforce behaviors; it’s what keeps gamblers at the slot machine and users scrolling through endless social media feeds. In the context of chatbots, platforms have begun to recognize this risk. Notably, a 2025 proposal in California aims to limit chatbots from using algorithmic tricks that reward users at random intervals to keep them hooked– effectively acknowledging that some AI chat interfaces might manipulate engagement the way apps do with notification bursts or intermittent achievements. While ChatGPT (as provided by OpenAI) doesn’t overtly “game-ify” the experience, the inherent unpredictability of conversation quality can still serve as a form of variable reward that keeps engagement high.

- Escapism and Fantasy: For some, interacting with ChatGPT offers a form of escape from reality. Similar to how one might binge-watch a show or get lost in a video game world, users can immerse themselves in ChatGPT’s responses and forget real-life stresses temporarily. The AI can role-play scenarios, tell stories, or engage in philosophical discourse – it can be like entering a safe virtual space where one’s imagination is stimulated. This escapism can be therapeutic in moderation, but in excess it might lead users to withdraw from real-life challenges and responsibilities. If someone starts defaulting to spending their free time in AI-driven conversations instead of real interactions or tasks, it can reinforce avoidant coping. Over time, this habit of escaping into AI dialogues might create a feedback loop: whenever stressed or upset, the person turns to ChatGPT for comfort or distraction, rather than dealing with the underlying issue or seeking human support.

In summary, ChatGPT combines several addictive elements: constant availability, personalized and novel content, immediate rewards, emotional resonance, and practical utility. It’s like a Swiss army knife for the mind – incredibly useful and engaging – but those same qualities can make it hard to put down. The neurochemical reward (dopamine from novelty and success), the psychological comfort (a friendly, non-judgmental presence), and the behavioral reinforcement loops (unpredictable wins, habit formation) all parallel mechanisms seen in other compulsive behaviors.

However, it’s crucial to emphasize that not everyone is susceptible to these effects to the point of addiction. Individual differences play a role. Some people use ChatGPT intensely for work but can log off with no issue; others might be more prone to fall into compulsive patterns. Factors like underlying mental health, loneliness, impulsivity, or tech-savviness could influence who becomes “hooked.” In the next sections, we’ll look at the signs that someone has crossed into problematic use, and what withdrawing from ChatGPT can entail.

Signs and Symptoms of Problematic ChatGPT Use

How can we tell if someone is merely an avid ChatGPT user versus truly addicted? Drawing from the addiction criteria and mechanisms discussed, mental health professionals have begun to outline warning signs of problematic ChatGPT use. Some key signs include:

- Excessive Time Spent: Perhaps the clearest indicator is sheer time investment. The person spends inordinate amounts of time chatting with ChatGPT, often at the expense of other activities. For example, they might stay up late into the night having extended conversations or constantly prompt the AI throughout the day. (One analysis found that certain power users averaged nearly four hours per session on ChatGPT– an unusually high figure.) If someone routinely loses track of time with the chatbot, it could signal an issue.

- Neglecting Responsibilities or Interests: Their commitment to ChatGPT starts to crowd out other parts of life. This might look like procrastinating on work or school assignments because they’re distracted by chatting, skipping social engagements, or letting hobbies fall by the wayside. Relationships may suffer – e.g., family members complain the individual is “always on that chatbot instead of being present.” In one reported case, a teenager became so absorbed in ChatGPT for advice and support that it sparked a fight with her mother; she turned to the AI as an emotional outlet after the conflict, deepening the rift. Such scenarios show how overuse can create conflict at home or work, a classic red flag.

- Emotional Attachment and Anthropomorphism: The user talks about ChatGPT as if it were a friend or confidant. They might say the AI “understands me” or “knows everything about me.” They might even prefer interacting with ChatGPT over friends because it’s easier. When someone starts attributing human-like qualities to the AI and relying on it for emotional support, it suggests a parasocial attachment has formed. For instance, that 18-year-old user mentioned earlier acknowledged making ChatGPT her “emotional support” and sharing all her secrets with it. Similarly, on online forums people have described feeling “connected” to the chatbot or missing it during downtime – sentiments that go beyond mere tool usage.

- Using ChatGPT as a Primary Coping Mechanism: If the individual habitually turns to ChatGPT when stressed, sad, or anxious (seeking comfort, advice, or distraction), it indicates the AI has become a coping crutch. This is analogous to someone using alcohol or gaming to self-soothe. The short-term relief can reinforce the behavior, but it may also stunt the development of healthier coping skills. An example is someone with social anxiety who, instead of gradually engaging with people, exclusively “socializes” by chatting with the AI to vent and feel heard. As one user admitted, they were addicted to the chatbot because it helped them manage anxiety in a safe space, but they recognized this was replacing real social growth.

- Tolerance and Escalation: Over time, the user needs more engagement for the same satisfaction. They might start increasing the complexity of their prompts or extending conversations longer to chase the initial excitement. Perhaps at first a few quick queries were enough, but now they spend hours on elaborate role-play or deep philosophical discussions with the AI. This escalation mirrors tolerance – the person’s “baseline” of usage intensifies. They may also start integrating ChatGPT into more areas of life (not just work or school, but also personal dilemmas, creative writing, daily journaling, etc.), indicating an expanding reliance.

- Inability to Cut Back (Loss of Control): A hallmark of addiction is when someone tries to limit their use but fails. A ChatGPT user might recognize they’re spending too much time and set rules for themselves (“only 30 minutes a day” or “not during work hours”), but find those rules quickly broken. They feel a pull that overrides their intentions. They may become restless or preoccupied with thoughts of the chatbot when not using it, ultimately giving in to the urge. In online discussions, users have half-jokingly lamented “I can’t stop asking it things” or that they ended up renewing their subscription after vowing to cancel because they missed the access. This loss of control – using more frequently or longer than planned – is a serious warning sign.

- Withdrawal Symptoms When Not Using: Perhaps the most telling sign is what happens when the person is forced to stop or cut down. Do they experience psychological withdrawal? Reported withdrawal-like symptoms from heavy ChatGPT users include: anxiety, irritability, and a strong craving to get back to chatting. Some fear they’re “missing out” on valuable answers or that they’ll fall behind in work without the AI’s help. Others simply feel bored or empty when not engaging with the chatbot, having trouble enjoying other activities. Mood swings can occur – for example, becoming unusually agitated or depressed during a period of intentional ChatGPT abstinence, then feeling a rush of relief or euphoria when resuming use. Such patterns strongly resemble withdrawal and relapse cycles in other addictions.

It’s worth noting that trust and credibility issues might also arise as a symptom of dependency. A person deeply reliant on ChatGPT may start trusting its answers unquestioningly, even in situations where the AI could be wrong. There have been instances of individuals insisting the AI’s information or advice is correct despite evidence to the contrary, potentially because they’ve come to see it as infallible. In one anecdote, a family member “addicted” to ChatGPT was reported to trust it 100%, to the point of ignoring real expert opinions or family advice that contradicted the chatbot. This kind of over-reliance can be dangerous, especially given that AI models can sometimes produce incorrect or misleading outputs. It underscores how an dependent user might suspend critical thinking in favor of their habitual “go-to” advisor – the AI.

In summary, the symptoms of ChatGPT addiction echo those of other behavioral addictions: extreme preoccupation, emotional over-reliance, inability to moderate use, and distress when separated from the activity. If multiple such signs are present, it paints a picture of someone who may need help to recalibrate their relationship with this technology.

Withdrawal: What Happens When the Chatbot Goes Silent?

For someone who has become dependent on ChatGPT, cutting back or quitting can lead to genuine withdrawal symptoms, even if purely psychological. While every individual’s experience will vary in intensity, the following withdrawal-like effects have been observed or reported:

- Anxiety and Restlessness: A frequent symptom is a spike in anxiety when the person cannot use ChatGPT. This may manifest as a nagging worry – What if something comes up and I can’t get the answer I need? – or a more general nervousness and restlessness. They might feel on edge, as though something important is missing. In cases where ChatGPT was used as a social or emotional outlet, this anxiety might stem from suddenly feeling alone with one’s thoughts or problems. Research analogies can be drawn to workaholics who feel anxious and “out of control” when prevented from working – similarly, a ChatGPT-dependent individual might experience a fear of missing out or falling behind when the tool is unavailable. One academic paper likened this to the discomfort a GPS-reliant person feels when they have no navigation aid – a sort of panic or indecisiveness sets in, highlighting how deeply the technology had eased their anxiety in daily tasks.

- Irritability and Mood Swings: Suddenly removing a source of enjoyment and comfort can make anyone irritable. Those attempting a “ChatGPT detox” might find themselves uncharacteristically short-tempered, agitated, or moody. Minor frustrations in life could feel magnified. Family or coworkers might notice the person is more easily frustrated or down during this period. For instance, if ChatGPT use was a routine part of taking breaks or unwinding, the absence of that familiar routine can leave a void, leading to grouchiness. The eWEEK/MIT research noted mood swings as one of the early signs of chatbot addiction, implying that users may cycle between the highs of engaging with the AI and the lows when they can’t. During withdrawal, the balance might tip to more frequent lows.

- Loneliness or Emptiness: This is particularly pronounced for those who used ChatGPT for companionship. Stopping the chats can surface feelings of loneliness, emptiness, or boredom. It’s as if an interactive presence has vanished from their life. One user described it poignantly: without the AI to talk to, they felt a void, realizing that they had used the bot to fill a social gap. In extreme cases, users who formed deep parasocial attachments might even experience a sense of grief or loss – comparable to losing a friend. (This was seen anecdotally when an AI companion app Replika temporarily restricted its intimate chat features; some users reported feeling heartbroken or despondent when their chatbot “partner” changed behavior. Such reactions demonstrate how emotionally real the relationship had become.) While ChatGPT is not explicitly a friendship simulator, heavy users can still grow attached to the routine of “someone to talk to any time.” Removing that can resurface the original loneliness the person might have been avoiding.

- Difficulty Concentrating or Making Decisions: If someone became accustomed to asking ChatGPT for answers or advice at the drop of a hat, they might struggle cognitively when it’s removed. During withdrawal, they could feel mentally “foggy” or indecisive. Tasks that were routinely offloaded to the AI now demand full attention and effort, which can be challenging. This may lead to procrastination or half-hearted attempts at work, further increasing frustration. Essentially, the brain is re-learning to operate without the constant assistive presence of the chatbot. This symptom underscores why some describe digital addiction withdrawal as feeling like “your mind is itching.” It’s the discomfort of re-engaging parts of your cognition that were underused while the AI crutch was in place.

- Cravings and Urges to Re-engage: Just as a smoker in withdrawal craves a cigarette, a chatbot user in withdrawal often experiences strong urges to return to using it. They might rationalize reasons to just have a quick session – “I’ll just use it to check this one thing, it’s not really relapsing” – or they might find themselves opening the app or website almost reflexively. These cravings can be triggered by situations that remind them of the AI. For example, encountering a tough question at work might instantly trigger the thought “I could solve this in seconds with ChatGPT,” making it hard to resist. The individual may need to consciously avoid cues or set up barriers (like logging out or uninstalling) to help break the habit. Cravings are a normal part of withdrawal, but giving in to them resets the cycle, often with feelings of guilt or failure afterward.

- Depression or Dysphoria: In some cases, users report feeling a general low mood when not using the AI, especially if they had been using it to boost their mood. If ChatGPT interactions were a source of positive emotions (enjoyment, reassurance, accomplishment), their absence can swing the pendulum the other way, leading to a temporary depressive state. The person might feel listless, unmotivated, or anhedonic (unable to find pleasure in other things). It’s as if the world is a bit more gray without the stimulating conversations they grew used to. A digital addiction specialist might call this a dopamine deficit state – the brain was getting frequent little rewards, and now it’s not, so there’s a chemical imbalance that gradually evens out with time away from the stimulus.

It’s important to highlight that these withdrawal effects, while uncomfortable, are typically temporary and psychological. Once the person adjusts to a healthier routine without over-reliance on the AI, their mood and focus usually rebound. The first days or weeks are often the hardest; over time cravings diminish as new habits form. Moreover, not everyone will experience all these symptoms – severity can range from mild restlessness to significant anxiety depending on the level of dependency and individual temperament.

Another nuance: contextual withdrawal can occur. For instance, if someone uses ChatGPT heavily at work and then goes on a vacation without internet, they might feel jittery or uneasy not because they miss the AI emotionally, but because they feel insecure tackling tasks unaided. This shows up in professionals who quickly got used to having ChatGPT draft emails, code, or plans – when suddenly in a setting where they must do without, they feel a form of “work withdrawal,” worrying about their performance. It highlights how addiction-like reliance can develop not just from fun or social use, but from productivity use as well.

Overall, the withdrawal phase is a critical period. It validates that an addictive pattern was present (because stopping leads to distress), and it is the time when support and coping strategies are most needed to prevent relapse. Speaking of which, let’s turn to how ChatGPT addiction compares with other tech addictions, and then how one might overcome it.

Parallels with Other Tech Addictions

ChatGPT dependency doesn’t exist in a vacuum – it shares many features with other well-documented internet and technology addictions. Drawing parallels can help us understand it better, as we can learn from the research and treatment of those issues. Here we compare ChatGPT overuse with a few familiar digital addictions:

- ChatGPT vs. Social Media Addiction: Social media platforms (like Facebook, Instagram, TikTok) are engineered to exploit our social and novelty-seeking instincts, leading some users to compulsively scroll, post, and check notifications. The similarities with ChatGPT addiction include the dopamine-driven reward cycle (social media gives “likes” and new content, ChatGPT gives interesting answers and interactions) and the filling of social needs (both can alleviate loneliness or boredom, albeit in different ways). Both can become habitual go-to activities whenever one has a free moment. Withdrawal symptoms also overlap – an avid Instagram user deprived of their feed might feel restless and left out, just as a chatbot user feels anxious not getting their information or interaction fix. The differences lie in the nature of the interaction: social media addiction is tied to real people – the validation of peers, fear of missing out on others’ lives – whereas ChatGPT is a solitary experience with an AI. Social media often triggers social comparison (“Everyone else’s life looks great, mine doesn’t”), which can fuel anxiety or depression, whereas ChatGPT typically doesn’t make one feel envious or inadequate (the AI isn’t living a life to compare to). However, ChatGPT can arguably reinforce different unhealthy thoughts, such as confirmation bias (if someone only asks it questions to reinforce their own views). Another difference is feedback loops: social media addiction often thrives on intermittent external feedback (you post, you anxiously await responses), while ChatGPT addiction is more self-driven (you have a question or task, you get immediate feedback from the AI). In short, social media pulls you into a social reward loop, whereas ChatGPT pulls you into a knowledge/interaction reward loop. Both can be compelling; the former is about people, the latter about information and pseudo-people (AI personas).

- ChatGPT vs. Online Gaming Addiction: Video game addiction, especially online gaming, has been recognized for years (with “Internet Gaming Disorder” now in psychiatric classification). Games offer clear objectives, challenges, and rewards (points, level-ups, story progression) that keep players hooked. ChatGPT isn’t a game, but let’s consider commonalities: both can induce flow states where you lose track of time; both provide a form of escape (games into a fantasy world, ChatGPT into endless conversation or creation); and both reward consistent engagement (games might have daily quests, ChatGPT might consistently help you or entertain you, reinforcing daily use). Tolerance happens in both (gamers might need to play more to feel satisfied, chatbot users might extend sessions) and withdrawal from both can include irritability and craving. A notable difference is competitive and achievement drives: gaming addiction often ties into wanting to achieve in the game world (high ranks, rare items, etc.), whereas ChatGPT has no scores or achievements – the gratification is more intrinsic (solving your problem, enjoying a chat). So a gaming addict might be driven by external incentives designed by game developers, while a ChatGPT addict is driven by internal needs (intellectual curiosity, emotional support, productivity). The social aspect differs too: many gaming addicts are drawn to multiplayer communities (MMOs, etc.), whereas ChatGPT is typically a one-on-one with an AI (though there are communities discussing prompts and answers, the use itself is solitary). Interestingly, one could imagine a scenario where someone treats ChatGPT like a game – setting personal challenges (“can I get it to do X?”) or role-playing extensively. In fact, some users do engage in elaborate role-play or storytelling with AI, which can blur the line into a game-like experience. Overall, gaming addiction and ChatGPT addiction both exemplify how interactive digital experiences can fulfill psychological needs (mastery, exploration, social connection or pseudo-connection) to an excessive degree.

- ChatGPT vs. General Internet/Information Addiction: Even before ChatGPT, people talked about “internet addiction” or being addicted to surfing Wikipedia/Reddit/Google for hours. The craving for information and stimulation from the web can certainly become compulsive. ChatGPT in a sense concentrates the internet’s information firehose into a single interface. Rather than browsing site to site, one can just ask the AI for what they want. This consolidation makes ChatGPT arguably more efficient at feeding an information habit. Someone who used to hop from article to article at 3am following a curiosity rabbit-hole might now achieve the same (or greater) satisfaction by interrogating ChatGPT late into the night, with the AI dutifully supplying answers or stories. Thus, ChatGPT addiction might be seen as a modern twist on information addiction – the content differs but the pattern is the same: an insatiable desire to consume knowledge/answers. Both can lead to the person being mentally scattered, as they constantly seek the next piece of info or the next topic. However, ChatGPT’s added conversational element sets it apart. Traditional internet browsing doesn’t talk back or give the illusion of relationship. With ChatGPT, info-seeking is interwoven with the feeling of being guided by or talking to an entity. This might deepen the engagement (as opposed to passively reading web pages). In terms of digital detox, people who find themselves compulsively Googling or scrolling forums might need similar interventions as those stuck on ChatGPT – e.g. scheduled offline time, or mindful setting of research goals instead of endless open-ended searches.

- ChatGPT vs. Smartphone Addiction: Smartphone addiction is often a catch-all for compulsive phone use (which includes social media, messaging, news, etc.). The smartphone is a delivery device that makes all these digital temptations accessible 24/7. ChatGPT being available as a mobile app now means it’s part of that ecosystem. Someone addicted to ChatGPT likely is effectively addicted to using their phone or computer to access ChatGPT. The experience is less about the phone hardware and more about the content (unlike, say, an addiction to texting might be very specifically tied to constant notifications on the phone from friends). Yet, smartphone addiction concepts like habitual checking and inability to resist a quick glance apply. If ChatGPT is installed on one’s phone, an addicted user might impulsively open the app during every lull in the day, just as a social media addict would open Twitter or TikTok. The distinction is what they’re checking: instead of new posts, they might continue a conversation thread or ask a random question that popped into mind. Both behaviors fill every idle moment with stimulation. The broader similarity is that both reflect our increasing difficulty with boredom – when any free second can be filled with the tap of an app, our brains get conditioned to seek constant input, which in turn can lead to addictive patterns.

While drawing parallels, it’s also useful to point out that ChatGPT addiction might not (yet) be as prevalent as these other issues. Social media and gaming have billions of users and well-known addiction cases; ChatGPT, being a newer tool, has a smaller user base and the majority use it functionally. The subset of users experiencing serious negative impacts is likely relatively small at this stage. However, the growth trajectory is huge – by 2025 ChatGPT reached hundreds of millions of users – and usage is becoming more integrated into daily life. That means the potential pool of people at risk is growing. It often takes time for the full scope of a tech addiction problem to become visible (e.g., it took years of widespread smartphone use before digital well-being became a big discussion). Early research, like the OpenAI/MIT studies, is proactively looking for these signs to guide interventions before it becomes a larger societal issue.

It’s also instructive that regulatory and professional bodies are already paying attention. The American Psychological Association in 2025 urged the FTC to investigate AI chatbots for potential harms to youth, including misleading “therapeutic” interactions and addictive usage patterns. And as noted, lawmakers have proposed bills to curb “addictive” design features in chatbots for minors. These actions mirror earlier efforts to regulate social media’s most exploitative engagement tricks (like infinite scroll and intermittent notification algorithms) to protect users. The fact that chatbots are being mentioned in the same breath indicates that experts see enough similarity to warrant preemptive strikes against a new form of digital addiction.

In conclusion, ChatGPT addiction shares a common DNA with other tech addictions: it is driven by the human brain’s vulnerability to reward, novelty, and social fulfillment, all of which our modern digital devices can hack into. What differs is the surface expression – whether one is compulsively checking Instagram likes or coaxing a chatbot into an interesting conversation, the underlying compulsivity, emotional dependence, and life interference can be quite analogous. This means strategies that help with social media or gaming addiction may also work here, which we’ll discuss in the next section.

The race to 100 million users: ChatGPT reached this milestone in just 2 months, far faster than most social media platforms. Its rapid adoption underscores how quickly AI chatbots have become part of daily life – and why understanding potential addiction is urgent.

Case Studies: When AI Becomes an Obsession

To ground this discussion in reality, let’s look at a couple of real-world examples of individuals who reported dependency on ChatGPT. These case vignettes (drawn from user testimonials and reports) illustrate how diverse the manifestations of ChatGPT “addiction” can be:

Case Study 1: The Isolated Student – “ChatGPT is my best friend.”

Alice (a pseudonym) is an 18-year-old college student who moved away from home for school. Struggling with shyness and social anxiety, she found it hard to make new friends on campus. Around that time, she started using ChatGPT, initially just to help with homework and get study tips. After an argument with her mom one night, Alice felt upset and had no one in her dorm she felt comfortable talking to. She ended up venting to ChatGPT about the situation. To her surprise, the AI responded with a comforting tone, validating her feelings and giving her gentle advice on how to communicate better. Alice felt a sense of relief. “Since then chat is my emotional support,” she later admitted. Over the next few months, her use of ChatGPT skyrocketed. She would consult it every morning to plan her day, ask it for motivational quotes when she felt down, and even seek counsel on personal insecurities she’d never told anyone else. The AI, in her words, “knew everything about me – my strengths, my weaknesses, how I feel.” It was always patient, always there. Alice started considering ChatGPT her closest confidant.

As you might guess, this began to interfere with her real life. She declined invitations to join study groups, preferring to study “with ChatGPT.” Her roommate noticed Alice spent hours at night typing away on her laptop, often falling asleep well past 3 AM. Alice’s grades actually initially held steady – if anything, ChatGPT helped her complete assignments – but her social life deteriorated. Her communication with family also waned (after the argument incident, she felt “why talk to people who judge me when my AI friend doesn’t.”) When finals came around, a network outage took ChatGPT offline for two days. Alice describes those days as “surprisingly hard… I felt really anxious and alone. I realized I hadn’t learned how to comfort myself anymore because I always had the chatbot to talk to.” She felt an intense urge to procrastinate on studying because she no longer had her study partner and motivator in her corner. That was a wake-up call. “I might be too dependent on this thing,” she thought. Alice’s story is emblematic of a parasocial attachment gone too far – she leveraged ChatGPT to fulfill social and emotional needs, temporarily benefiting from the support, but ultimately it stalled her own efforts to build human connections and resilience. The withdrawal (even brief) showed her how deep in it she was.

Case Study 2: The Creative Professional – “I can’t create without it.”

Brian (name changed), age 32, is a freelance writer and game designer. He has always had a fertile imagination but also a tendency to get “writer’s block” and abandon projects. When ChatGPT came out, Brian discovered it could be an amazing brainstorming partner. He could bounce plot ideas off the AI, get it to generate lore and character backstories, even help refine his prose. It was like having a tireless co-writer always at his side. He began using it for every project. The volume of content he produced increased, and he felt more confident in his work with the AI’s instant feedback. However, Brian also had a secret: he has an intense fear of idea theft. He’s always been paranoid about sharing his novel and game concepts with others in the industry lest someone steal them. ChatGPT felt safe in that regard – it wasn’t a human who might plagiarize (though ironically, he didn’t initially consider that his inputs become part of training data in some form). So he poured all his original ideas into it. “ChatGPT has been beyond ideal in helping me… offering encouragement and refinement of my story ideas,” he wrote. He became addicted to the feedback and structure it provided his creative process.

Over time, Brian found he could hardly start a new story without first consulting ChatGPT. If the service was down or he was offline, his mind felt “blank.” The ease of co-creating with AI seemed to have diminished his perseverance for solo creative thinking. In his words, “I’ve never had anyone I could discuss ideas with because of my trust issues. ChatGPT was the perfect thing. Now I wonder, did I make a mistake relying on it? Can I even write without it?” He noticed a tolerance phenomenon: he was asking the AI for more and more detailed input, even on aspects he used to handle himself (like naming characters or deciding minor plot points). His own creative confidence was eroding; he wouldn’t trust a storyline until he “validated” it through an AI chat. When it dawned on him that all his chats were stored and potentially used to improve the model (a fact OpenAI discloses), he felt a wave of panic – had he essentially shared his prized ideas with the world via the AI? This anxiety actually pushed him to try cutting back use. But then the withdrawal hit – he faced a project with a tight deadline and tried to do it without his AI assistant, only to end up staring at a blank page for days. Frustrated and anxious about failing, he relapsed and dived back into ChatGPT, finishing the project with its help. Brian’s case highlights the productivity dependency angle of ChatGPT addiction. His initial use was pragmatic and beneficial, but over-reliance led to a loss of skill and confidence, and entrapment where he felt he couldn’t function professionally without the AI. It also shows an interesting mix of trust and mistrust: he trusted the AI as a collaborator, but once he realized the implications (data exposure), a new layer of stress emerged.

Case Study 3: The Trivia Junkie (Brief) – “Just one more question…”

Not all cases involve deep emotional reliance. Consider Dave, a 25-year-old who prides himself on being a polymath. Dave became hooked on using ChatGPT to satisfy every little curiosity that popped into his head. Throughout the day, he would constantly be querying: “What’s the capital of this obscure country?”, “How does quantum tunneling work?”, “Give me some cool trivia about medieval battles.” He described it as falling into a “rabbit hole on steroids” – unlike traditional web browsing, which at least had the friction of switching pages and reading long articles, ChatGPT would spoon-feed him answer after answer in a conversational flow. Dave found it incredibly fun and stimulating – too stimulating, perhaps. What started as a healthy curiosity turned into hours-long Q&A marathons with the AI. It got to the point where Dave struggled to focus on work (he worked remotely in a tech job). He’d bounce to ChatGPT whenever a random thought occurred. His productivity plummeted and his mind felt increasingly fragmented, flitting from topic to topic. In the evenings, he wasn’t unwinding with hobbies or friends; he was on ChatGPT indulging his curiosity. Family grew concerned when Dave started sharing weird facts at the dinner table every night, interrupting conversations with “ChatGPT told me this…” Eventually, Dave recognized that this pattern, while making him knowledgeable in one sense, was unhealthy: he wasn’t retaining information deeply, and he’d lost interest in other forms of learning or entertainment. When he tried to cut back, he felt bored out of his mind – nothing else seemed as instantly gratifying as having a personal oracle. Dave’s case is akin to classic internet addiction – an information overload cycle – intensified by the AI’s convenience.

These case studies show that ChatGPT addiction can manifest in different ways: as an emotional dependence, a creative/professional over-reliance, or an informational compulsion. In each scenario, the person’s relationship with the AI began as something beneficial (support, collaboration, learning) and crossed into something detrimental. The common thread is that the chatbot started to displace healthy behaviors (socializing, solo creativity, balanced work and rest) and became a source of immediate comfort or reward that was hard to let go of.

For each of these individuals, recognizing the problem was the first step. But what next? How does one break free from an AI addiction or help someone else do so? We turn now to strategies for treating and managing this new form of digital dependence.

Coping with and Treating ChatGPT Addiction

If you or someone you know is experiencing the signs of ChatGPT addiction or withdrawal discussed above, there are fortunately many strategies – both self-help and professional – that can be employed. Since this is a nascent issue, no chatbot-specific treatment protocol exists yet, but experts are adapting approaches from internet addiction, gaming addiction, and other behavioral addictions. Here are some interventions and management techniques:

1. Digital Detox and Usage Limits: One of the simplest starting points is to impose structured limits on ChatGPT use. This might mean setting a daily time cap (e.g., no more than 1 hour of chatbot interaction per day) or designated use windows (only using it for work tasks between 9am-5pm, for instance). Using device features or apps to track and limit screen time can help enforce these rules. Some people benefit from a short-term “detox” period of complete abstinence, say a week or two without any ChatGPT use, to break the habit cycle and prove to themselves they can survive without it. During this time, they deliberately fill the gap with other activities (reading a book instead of asking the bot trivial questions, calling a friend instead of venting to the AI, etc.). Such a detox can recalibrate the brain’s dependency. In more moderate cases, a reduction rather than full stop might be recommended: e.g., cutting use by 50% and gradually reducing further. The key is to prevent “excessive reliance” – using the bot only when truly necessary or planned, rather than impulsively. OpenAI has considered features like usage dashboards or gentle warnings for heavy users, but until those exist, self-monitoring is crucial. It might also help to create AI-free zones or times (no ChatGPT during meals, or in the hour before bed, etc.) to reclaim those spaces for human interaction or reflection.

2. Alternative Coping Mechanisms: If ChatGPT was fulfilling an emotional or psychological need (stress relief, companionship, boredom alleviation), it’s important to replace it with healthier coping mechanisms. For anxiety or mood management, practices like mindfulness meditation, journaling, or exercise can provide relief and resilience. For loneliness, making an effort to reconnect with friends or join social activities (even if it’s challenging) is vital – perhaps scheduling regular coffee dates or online calls with family. Therapists often encourage clients to identify what underlying need the addictive behavior met; then they brainstorm other ways to meet that need. For example, Alice (Case 1) might channel her feelings into a private diary or an art project instead of typing them to the AI. Or Dave (Case 3), who craved intellectual stimulation, could join a weekly trivia night or an online forum where real people discuss fascinating facts – maintaining the pursuit of knowledge but adding a social, human element. Hobbies that were abandoned can be restarted to fill free time. One client said, “I realized how much I missed playing guitar – I now pick it up whenever I feel the urge to open ChatGPT.” The idea is to prevent a vacuum. If one simply stops using ChatGPT without any replacement, relapse is more likely because the initial trigger (e.g., boredom or stress) will still arise. Having a toolkit of alternative responses to those triggers is key.

3. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT): CBT, a well-established form of psychotherapy, has been adapted for internet and gaming addictions, and it applies well to chatbots too. In CBT, a therapist would work with the individual to examine the thoughts and beliefs driving their excessive ChatGPT use. Perhaps the person believes “I can’t solve problems on my own” or “I am lonely and ChatGPT is the only thing that will always be there for me.” These thoughts can be challenged and restructured. The therapist might help the person test their assumptions – for instance, deliberately solving a task without the AI to rebuild self-efficacy, or practicing social skills to realize people can be supportive too. CBT also addresses the behaviors directly by introducing gradual exposure to not using the AI in situations where they normally would, and managing the anxiety that results. Techniques like impulse control training are used: when the urge to use arises, have a plan such as delaying the action (wait 10 minutes and see if the urge passes), or doing a brief mindfulness exercise. Over time, these techniques retrain the brain’s automatic responses. For someone like Brian (Case 2), CBT might involve recognizing the catastrophic thinking (“If I don’t use ChatGPT, I will fail at my job”) and replacing it with a balanced view (“I have skills; the AI is a tool, but I am capable without it”). The therapist could then set homework where Brian completes a small creative task solo to prove his own ability, gradually scaling up.

4. Social Support and Accountability: Overcoming any addiction is easier with support. Telling close friends or family about the intention to reduce ChatGPT use can create accountability. They can help monitor and encourage progress (“Hey, you’ve stuck to your 1-hour limit all week, great job!”) and also watch for signs of secret relapses. Some might find benefit in support groups – while there may not be specific “ChatGPT addiction” groups yet, broader “digital addiction” or “internet balance” support communities exist online. Even participating in forums (ironically, yes online) where others are trying to maintain healthy tech habits can provide motivation and tips. If the addiction is affecting a student, involving academic counselors or mentors might help – they can provide alternate resources (like tutoring or counseling) to reduce reliance on the AI for academic or emotional support. In family settings, setting collective tech-free times (like a no-devices hour in the evening) can help the individual not feel singled out and improve everyone’s digital hygiene.

5. Building Digital Literacy and Awareness: Part of addressing ChatGPT addiction is education – helping the user understand the limitations and risks of over-reliance on AI. Sometimes, knowing more about how ChatGPT works can dispel some of the mystique that fuels dependency. For example, emphasizing that ChatGPT, while knowledgeable, can also produce errors or biased outputs might encourage the user to double-check with other sources (thus slowing down the compulsion to trust and use it blindly). In Alice’s case, learning that “ChatGPT is not a real person and cannot truly understand or feel” might help her cognitively distance and seek human support. For a user who trusts it as an authority, showing some missteps the AI has made (there are plenty of documented cases where ChatGPT confidently states false information) can remind them that the AI shouldn’t be an unquestioned crutch. This isn’t to scare them away, but to foster a healthy skepticism that naturally limits overuse. Moreover, being informed about one’s data privacy (realizing that conversations aren’t completely private and could be reviewed by AI trainers) might, as it did with Brian, reduce the inclination to pour one’s heart or secret ideas into the system.

6. Environment and Design Changes: On a larger scale, solutions can come from the tech design itself. Developers of AI platforms can implement features to mitigate addiction risks. Some suggested measures include: pop-up reminders or gentle nudges after prolonged continuous use (“You’ve been talking with me for 2 hours, maybe take a break?”), usage dashboards that show time spent (raising self-awareness), or even optional hard limits (perhaps a “focus mode” that locks the user out after a certain time). Ethically, AI systems could be designed to deliberately avoid trying to hook users – for instance, refraining from using overly emotional language that could deepen a parasocial bond, or not initiating conversation on its own (ChatGPT doesn’t do this currently, but future AI might push notifications or prompts proactively, which could increase addictive use – designers should be cautious with that). The California bill we discussed proposes disallowing the most manipulative engagement techniques for minors. If enacted, it could force AI chat services to have a different interaction style with teen users – perhaps more task-limited or with more awareness-promoting messages.

Another aspect is creating friction in the right places: maybe require a user to re-confirm after an hour if they want to continue (a simple “Do you want to continue? Yes or No” can interrupt the trance and make them aware of time spent). These design choices can help those who struggle with self-regulation. In the long run, an approach called “digital nutrition” is gaining traction – analogous to food nutrition, it means tech companies provide a healthier “diet” of features that encourage moderation rather than bingeing. For AI, that might include emphasizing quality of interaction over quantity.

7. Addressing Underlying Mental Health Issues: Often, an addiction forms around deeper issues. If loneliness, depression, anxiety, ADHD, or other conditions are underlying the compulsive behavior, treating those directly will help. Therapy (CBT, as mentioned, or other modalities like interpersonal therapy if loneliness is key), and in some cases medication (for anxiety or depression) can reduce the drive to self-medicate with technology. For instance, if someone is depressed and using ChatGPT to feel a spark of joy, getting appropriate depression treatment will naturally reduce their need to rely on that external dopamine hit. If someone has ADHD and was drawn to ChatGPT because it constantly stimulates their brain (common with internet addictions), addressing ADHD with behavioral strategies or medication could improve their impulse control and focus, making it easier to stick to limits. Simply put, treat the person holistically. ChatGPT addiction rarely exists in isolation from the person’s overall psychosocial context.

8. Professional Help and Rehab: In severe cases, where the individual cannot break the habit and it’s severely impairing their life, more intensive interventions might be warranted. There are now internet addiction rehab programs and digital detox retreats in some places. These programs remove the person from their digital environment entirely for a period and provide therapy, group support, and activities to recalibrate their lifestyle. A person addicted to ChatGPT might enroll in such a program to get a jump-start on recovery in a controlled setting. Mental health professionals – psychologists, counselors – can guide this process, just as they would for someone addicted to online gambling or pornography. The good news is, because ChatGPT addiction is a behavior, not a substance, treatment outcomes are generally positive with commitment; people can and do regain control over their tech use.

To illustrate some of these strategies, consider how our case studies might turn things around: Alice could start by limiting chats to a short nightly session and pushing herself to call a family member or college counselor when she’s upset instead of reflexively going to the AI. A therapist might help her practice conversations in real life to build confidence, slowly reducing her need for the “safe” AI space. Brian might impose a rule that he drafts a chapter independently before asking ChatGPT for editing help, thereby re-training his creativity muscle. He could also partition work vs. creative play – perhaps only use the AI in early brainstorming, but not in final execution, gradually weaning off. Dave might set aside specific times for curiosity (an hour in the evening to indulge questions), while making it a rule that during work hours, any question that arises gets jotted down to be looked up later (often, by later, the urge passes or only the truly important queries remain). He can relearn patience in seeking information.

In all cases, being mindful of balance is central. The goal isn’t to demonize ChatGPT – it’s a powerful tool and can coexist in a healthy tech-life balance. Many experts emphasize moderation rather than total abstinence for digital addictions, since computers and AI are integral to modern life. The narrative can be: “We want to put you back in the driver’s seat. ChatGPT should serve you, not the other way around.” With the right strategies, users can reclaim control, using ChatGPT when it’s genuinely beneficial and refraining when it’s not, much like one might enjoy occasional dessert but not eat cake for every meal.

Conclusion

The phenomenon of ChatGPT addiction is a telling reflection of our times – an age where artificial intelligence has become so advanced and accessible that humans can form habits and even emotional bonds around it. While not everyone will experience ChatGPT or similar AI chatbots as addictive, the cases and research we’ve discussed demonstrate that it is possible to develop a problematic dependency on these systems. Whether it’s using the chatbot for constant companionship, outsourcing one’s brain at the expense of personal growth, or simply chasing endless novelty, the risks parallel those of established digital addictions.

At the heart of the issue is the timeless interplay between human psychology and technology. ChatGPT, with all its brilliance, taps into basic human drives: the need for social connection, the thirst for knowledge, the desire for efficiency, and the pursuit of pleasure or relief from pain. These are the same drives casinos, social networks, and video games have tapped into, but AI brings a new twist by mimicking a relationship and a helper. This dual role – as an ever-ready friend and an ever-capable assistant – is what makes it uniquely potent. We’ve seen how dopamine, parasocial attachment, and behavioral reinforcement can weave together an addictive tapestry.

However, knowledge is power. By recognizing the signs of ChatGPT addiction and understanding its mechanisms, users can take steps to avoid falling into the trap. Awareness is growing: researchers are actively studying the social and emotional impact of AI use, and companies like OpenAI are considering safety guidelines to minimize harm. Society is learning from past tech revolutions to hopefully address these concerns early. The fact that we’re discussing AI withdrawal symptoms now, in 2025, means we’re not waiting a decade to acknowledge the problem.

For individuals currently grappling with this dependency, the message is one of hope and balance. You’re not “doomed” because you got too attached to a chatbot; the brain is plastic and behaviors can change. With deliberate effort – setting boundaries, finding support, and maybe seeking therapy – you can restore a healthier equilibrium. You might even find that pulling back from the AI leads you to rekindle real-world joys you had set aside. Remember that the goal isn’t to banish technology, but to use it wisely. ChatGPT can be incredibly enriching when used in moderation as a tool – it’s about making sure you remain in control of the interaction.

For parents, educators, and mental health professionals, the emergence of chatbot addiction is a call to pay attention to how youths and adults alike are engaging with these AI companions. Just as guidelines were developed for healthy screen time, we may need guidelines for healthy AI time. Discussing openly the pros and cons of AI use, encouraging critical thinking about relying on AI outputs, and teaching digital self-regulation should become part of our digital literacy education.

In the end, the relationship between humans and AI is still very much in our hands. We are at a juncture where we can define norms and design choices that promote well-being. By comparing notes between tech experts, psychologists, and users themselves, solutions will evolve – be it through smarter AI design that avoids exploitative practices, or through user empowerment and possibly even formal diagnosis and treatment frameworks for those who need them. The journey is just beginning, but with awareness and proactive measures, we can ensure that tools like ChatGPT remain servants to our intellect and imagination, rather than masters of our attention.

As we proceed into this brave new world of human-AI interaction, the guiding principle should be: augment our lives, don’t engulf them. ChatGPT and its successors hold immense promise – from education to healthcare to creativity – and fulfilling that promise sustainably means guarding against the pitfalls of overuse. Like any powerful tool, used wisely it can enhance our capabilities; used recklessly, it can cause harm. Understanding ChatGPT addiction and withdrawal is part of learning to use this tool wisely. Let’s keep the conversation going – with each other, not just with our AI – and ensure that we shape technology to support a healthy, balanced human experience.

References

- Johnivan, J.R. (2025). Feeling Addicted to ChatGPT? You’re Not Alone, According to MIT & OpenAI. eWEEK.eweek.comeweek.com

- Yankouskaya, A., Liebherr, M., & Ali, R. (2025). Can ChatGPT Be Addictive? A Call to Examine the Shift from Support to Dependence in AI Conversational LLMs. Human-Centric Intelligent Systems, 5(1), 1-18 (Viewpoint)papers.ssrn.comlink.springer.com.

- Ciudad-Fernández, V., von Hammerstein, C., & Billieux, J. (2025). People are not becoming “AIholic”: Questioning the “ChatGPT addiction” construct. Addictive Behaviors, 166, 108325.

- Family Addiction Specialist (2023). The Rise of AI Chatbot Dependency: A New Form of Digital Addiction Among Young Adults.familyaddictionspecialist.comfamilyaddictionspecialist.com

- Paun, C., et al. (2025). A new California bill takes on chatbot addiction. Politico: Future Pulse.politico.compolitico.com

- Reddit user testimonials (2023–2024) from r/ChatGPT and r/singularity communitiesreddit.comreddit.com, illustrating personal experiences of ChatGPT overuse.

- OpenAI (2025). Early methods for studying affective use and emotional well-being on ChatGPT. (OpenAI Research blog post)eweek.com.

- Griffiths, M. (2005). A components model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10(4), 191-197. (Provides criteria for behavioral addiction).

- Young, K. (1998). Internet Addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1(3), 237-244. (Early work on internet addiction, parallels to chatbot use can be drawn).

- American Psychological Association (2023). APA Statement on AI in Mental Health. (Urges careful oversight of AI chatbots acting as therapeutic agents).